A Conversation with Craig Goodworth, Featured Artist

with Dave Mehler for TCR

Editorial Introduction: Craig Goodworth, an Oregon-based artist working in installation and poetry, often situates his art making at physical, disciplinary, and spiritual ecotones—the liminal spaces between two ecosystems. According to ecologists, ecotones often hold the most biodiversity. They teem with life, as creatures thrive amongst the abundant resources of both water and land, for example, or prairie and forest. Ecotones are also fraught with danger, however: land creatures can only spend so much time in the water, and unseen dangers can lurk below the surface. Creating art in such liminal spaces enables a richness and fecundity of materials and inspirations, but also requires hard work from the artist—some in his interior landscape, some in the exterior, physical landscape, and some in the relational world of society and academia. His practice encompasses drawing, object-making, research, teaching, and farm labor. He has received fellowships in art and writing, including a Fulbright Fellowship to the Slovak Republic (2015). Along with exhibiting his artwork nationally and internationally, he’s engaged in various collaborations and residencies relating art to science and religion. Goodworth holds master’s degrees in fine art and sustainable communities. His art includes themes of land, place, mysticism, and folk traditions. Influenced by time spent at an Eastern Orthodox monastery and finding a home in Quakerism, Goodworth maintains an active art practice through exhibitions, lectures/readings, and various artist residencies. A native of Arizona, Goodworth has spent much of his life in the West. Influenced by the desert landscape of the American Southwest and the fertile Willamette Valley of Oregon, he also delves into his connection with the landscape and culture of his ancestors in Eastern Europe. In recent years, his art has explored environmental topics both social and ecological: the experience of human immigration and its ecological and justice connotations, the aesthetic qualities of bees and honey as well as the ecological concern of hive collapse, and the power and horror of wildfires. He returns again and again in his art to the theme of the body: the individual body and interior landscape of the self, and the connection between and responsibility to the broader body of the Earth and its community of life.

………………..

TCR: First I need to point out to readers that we know each other and are friends, live in the same town and workshop poetry together. The reason this might be pertinent is that the interview is casually long and relaxed and stayed this way because I insisted we leave it that way against your better judgment to chop it down to a reasonable more formal length. It’s my belief that you, what you do and have to say about it is very interesting. So, first question:

How did you find yourself moving from a football scholarship to West Point to a practicing artist? I’d be really interested in hearing how that progression took place. And go back as far as you need to the beginnings of an artistic impulse, and why you pulled back at the last minute from an athletic track and military career that you were plainly on?

CG: Beauty first touched my life in the desert. Then through horses, then baseball. Regarding the latter, I gave myself fully to the rigor and the discipline, to the poetry and the craft of the game. When I threw my arm out at sixteen, it was a big wound. I loved baseball, but baseball didn’t love me back. Despite undergoing the Tommy John surgery, I never did recover. It felt like a kind of betrayal. At seventeen I got arrested doing stupid shit with my buddies and sent to military school back East. I got through it reading books. And when I did not have too many demerits, I got to go see other parts of the US on weekend leave with other Cadets. About this time, JD Salinger was really important to me. As was an uncle on a small farm in western PA.

When I got back for my final year of High School football, I entered the brutality of football. As a defensive end, I liked to hit. I liked the bull rush. I just had the raw material, and got all kinds of attention. And I didn’t have any other card play, (When you ain’t got nothin,’ you got nothin’ to lose–Dylan). When a West Point recruiter came to my house, my folks said: “Hell, you can have him right now, take him with you, get him the hell out of here.” I was all set to go football then Army, when a scar on my eye from getting hit at military school, needed a medical waiver. West Point didn’t have any left that year. They said to take a full ride somewhere else, lift weights, take college chemistry and get ready to come in the following year.

So I took a full ride to Boise State. In between three-a-day football practices, I’d go to the library and lie down between the library stacks and read Steinbeck, Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories and especially Kerouac who played football. Just biding my time in Idaho waiting to go to West Point suddenly did not seem that interesting. There was some legal stuff with the NCAA and for a while I wasn’t at either college. By the time it got resolved, boot camp, then pre-season interrupted me and “Joni Mitchell” (my girlfriend) living on the Oregon coast where I was reading books and smoking cigarettes. I took a flight, then a bus then a cab to the City and detoured to the Waldorf Astoria. I got to West Point in the middle of the night. The security guard payed the cab fare. I went to bed. Before I knew it, some boy man with rank and a clipboard kicked the door open, started shouting at me. I kicked the door shut. After the kicking of the door I was brazen enough to quote Bob Dylan to the commandant. That was the day I stopped being an athlete.

Looking back on it, West Point could’ve got me had they showed me the aesthetics, the ritual, the weight of tradition, sacrifice, and some real authority and solidarity. Instead, they recruited me wrong. They showed me Ford Mustangs, opportunities to get out of the military commitment coaching football, and creatine muscle head football players with pimples and Asian tutors. There was no way in hell I could give the next ten years of my life to locker rooms and barracks.

I Greyhounded to my Uncle’s farm and stayed a few months. Then after bouncing from a couple colleges, got myself a scholarship to art school.

I can say this: everything about craft, discipline, work, I learned as an athlete before I came to it in art. I learned it through practice. I learned it through coaches, through teammates and I learned it alone. I still believe in it. Hell, I weigh it heavy enough to coach my kids’ little league.

I’ve got this friend, a former student, who just signed up with the airforce to give his life to flying F-16s. I told him once that there’s some part of me somewhere that grieves not having been a soldier. He told me he thought I would have been wasted.

So I am the guy that had a lot of shit thrown at him early. If I had a redo, I could see myself playing my cards a lot of different ways. So to answer your question, the reason I stopped being an athlete is because I could no longer devote myself to what I loved. No matter how else it would have played out I know it would have needed a lot of meaning and just as much beauty.

………………..

TCR: You like to think of yourself as an elk, and not only an elk, but the stag from one of Aesop’s fables who is being driven by hounds and hunters finding temporary sanctuary and respite in a barn full of oxen where he hides a little too long eating grain out of the trough with domesticated animals until eventually his antlers give him away to the farmer and he’s shot.

You also are fond of referring to yourself as an ’embodied ecotone:’ bouncing between Quaker and Orthodox monk or pilgrim. Are we beasts and angels? Wanderers and sojourners with no true home? Would you care to take a moment in unpacking some of this?

CG: Sure. I think animal nature clarifies human nature. And maybe we tend to forget that. There are a couple of Aesop’s fables with stags that I’ve thought some about. But besides all that, my maternal ancestry is in Slovakia from the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains. There is this folk tale about a boy who nobody could get to sleep. His father went out in the forest and got one of those old-world stags, brought him into the boy’s room, and placed his son in the basket of the antlers. That image is maybe more complicated than Aesop – the wild animal nurturing the boy. Biologically antlers are about generativity and evidence of excess life. It’s sterile bulls that don’t shed. And yes in terms of Aesop, I do oftentimes get worried I’m overstaying my time in the barn and it could cost me.

I come from a long line of loggers, shepherds, and millworkers. Folks who don’t so much have bodies, as are their bodies. Growing up in Arizona I’ve been marked for better or worse by the mythos of the American west. There is a lot of brutality and tenderness, both pride and shame that comes from it. To answer your question, I think we are beasts. I don’t think you can say anything bad enough about human beings. And yet there are occasions of agape and unspeakable tenderness when one can’t say anything good enough either. I have as strong a proclivity towards whiskey as prayer. And to dominate as to participate. As I write these words, I am looking across the room at a milk-white porcelain and steel sculpture a friend made of a ravaged human torso–headless, armless, legless. A mutilated fragment with a single wing bound to it. Maybe the sculpture says it better than my words.

Regarding your question about ecotone, it is a word I use often to describe my work (art, labor, and teaching work), and it is an important concept in ecology. I find it symbolically meaningful to imagine the confluence of these actions as an ecotone. In ecology, an ecotone refers to the transition between two landscapes. The boundary can be clear and defined, or complicated and ambiguous.

My art mirrors an ecotone by crossing boundaries between farm labor and land art, installation, and poetry. And my art crosses boundaries in terms of audiences, both high and low culture. About five years ago, under a Fulbright, I ran around in the Carpathian forest researching and boozing with hunters and loggers, then put on some real nice clothes and took my wife and two small children to Bratislava, Slovakia where we ate turkey dinner at the American Ambassador’s table. Issue #24 (Liptovský Hrádok, Slovakia (In his office a forest boss talks to an American)

I’ve learned as much from Orthodox monks as I have Quakers. And I think about each better, in relation to the other.

Kosť & Med (Bone & Honey) 2016

Kosť & Med (Bone & Honey) 2016

Whitman talked about containing multitudes, I think most of us, especially artists hold contradictions. And as an artist I may be more conscious of it. And in the last decade I’ve been asking myself, what can I make of the contradictory multitudes I embody? In our divided times, what might the artist as embodied ecotone enable?

The ecotone of my spiritual, intellectual and artistic biography has afforded rich sources of nourishment, yet it is not always safe, obvious or familiar ground. I am interested in art that does “more than just sit on it’s ass in a museum” (Oldenburg) and happens outside the center, in empty landscapes. I want my poems to hold up in colleges and coffee shops and I want to think they would hold up in prisons. Art enables me to be with various kinds of folk, participating in both high and low culture.

“The boundary is the best place for acquiring knowledge” observed Paul Tillich. The boundary is about the only place I can breathe. It’s out of spiritual necessity, I straddle this ground. I’m a species that fits in the middle. Whatever else my soul may be, it is feral.

………………..

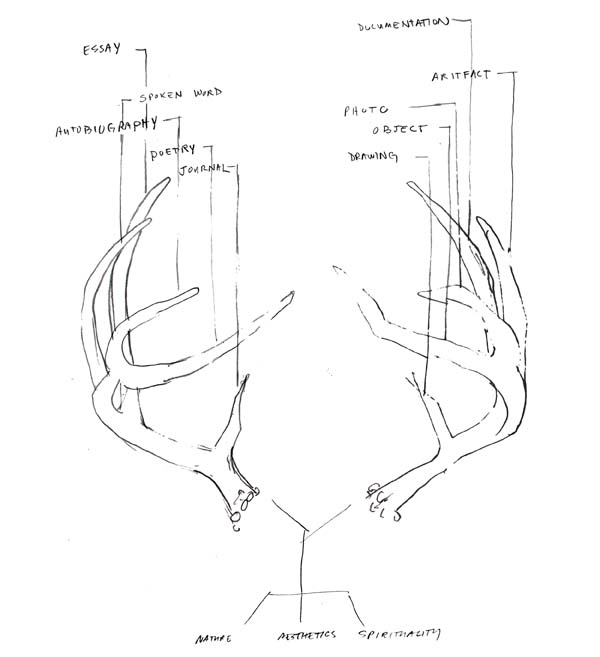

Craig Goodworth, Antler Schema, 2010

Craig Goodworth, Antler Schema, 2010

TCR: I noticed a diagram of antlers as a symbol for your practice—can you talk a bit about that?

CG: The first one I found was in the pear orchard on my Grandfather’s farm, I asked my uncle how the deer died. He told me the deer was not dead, that finding an antler is different than finding a bone. I kept that antler. I even slept with it.

In his book “Art Practice as Research,” Graham Sullivan provides the image/metaphor of a three stranded rope to describe arts-based research. The anatomy and life cycle of antlers is the metaphor for my practice.

At the risk of overusing the metaphor, I notice the following:

The pair of antlers balance and can clarify one another. The left antler corresponds to the different kinds of art I generate. The right antler represents my work with words. Working in visual art and working with words enables me to hold together instinct and ritual with story and metaphor. If I don’t nurture the growth of both antlers, my practice loses proportion and balance. In short, I need words, and I need to get beyond words.

Just as antlers grow incrementally starting with velvet in the Spring, calcifying in early Fall and shedding in late Winter, different seasons generate different kinds of art in my studio and writing practice. There is a necessary physicality—the raking, thrashing, and spearing of rut— followed by the slowing of winter. This parallels intense studio making followed by reflection from and writing about what got made.

I like knowing that elk in Arizona and New Mexico shed during Lent. That is, that there could be a relationship with nature’s rhythms, liturgical time and the gestation and bringing forth of art.

Finally, the antler metaphor helps me understand my place in a long robust tradition of honoring the continuum of humans within the rest of nature. From my ancestors in the Tatra mountains of Eastern Europe, to the American Transcendentalists, the contemporary nature writers, artists and theologians. I’m at least an animal drawn to grounded practices more as an effort to renew my humanity rather than transcend it. I’m more interested in becoming fully human rather than a woo-woo spiritual elf or angel and immortal which distorts or cheapens spirituality. The sour sweet tragic, honest elements rather than pretending we’re not going to rot and become humus. There’s that interview where Jackson Pollack is asked how nature factors into his work and he replies, “I am nature.”

………………..

TCR: Lets’ talk a bit about the western aesthetic. When I lived in eastern Oregon, an old buckaroo in late 80’s lamented the coming of barb wire, didn’t want to see the endless miles of gravel road paved (I was an outsider who thought he was nuts)—we were 135 miles from the nearest 5K pop town! We hosted a Chinese student who would watch with relish any American films but westerns—he found them stupid and boring. The current divide in our country is between city and rural dwellers—this conflict has gone on for thousands of years. There has been a mystique about the frontier and the west for 250 years—it has to do with open uninhabited spaces and uncivilized, untainted wilderness areas and perhaps lawlessness? It’s one of our major mythos’ in this country, and it’s infectious even to Europe as we’ve seen Sergio Leone and Ennio Morricone romanticize and mine our civil war and the West perhaps better than we have, and German tourists flock to our deserts in the southwest. Part of the reason for the devastating wildfires is because people are building and living right up against our remaining and dwindling wilderness areas. Rick Bass has written essays lamenting the national park service and how they carve them up with roads and allow people to penetrate areas of land which drives our large predators and essentially destroys the eco-system. We both read and enjoy Cormac McCarthy, who mines this mythos as well. You feel boxed in in your ‘ticky tack’ house fenced in and surrounded by houses in our 25K population town in lush Oregon wine country and are hoping to head back home to Arizona where you will be able to breathe again.

Given this long random opening, tell me what your ‘western aesthetic’ is, and why and how is that mythos important to you?

CG: At the Maryland Institute College of Art, I got to know the philosopher in residence, an Episcopalian priest pretty well. Apparently, he was defending me to one of my teachers saying the only way to understand Craig is to understand he’s from the desert. I’m not sure I know what he meant by it. It probably had something to do with my sense of scale and space, a general suspicion of authority, and perhaps some mythic trappings in my personality and my cowboy boots. Anyway, to the degree I’m conscious of having a “western aesthetic” (and I’m sure I do), it’s at least informed by the following:

Landscape

First, growing up in the Sonoran Desert, the desert was where you went to drink beer, shoot guns, maybe hunt quail. It was where you found dead bodies and people got shot in their pickup trucks and burned. This literally happened later to one of the foster children who lived in our house. Nevertheless, I feel more grounded in deserts than anywhere else. The sense of scale and space are just different in a desert. In an open landscape (as opposed to a closed) some feel powerless because of the ability to be seen. But at the same time, you at least have a shot at seeing any threat coming.

Secondly, there’s the land art of the 1960s and 1970s that pushed against the limits of sculpture. These guys worked directly in the landscape making earthworks on a very large scale in the desolate desert landscapes of the American Southwest. I get a lot of this art instinctually. Land-based art, working directly in the landscape, is where the desert and Western geography is most literally evident in my work. Excluding Slovakia and my grandfather’s farm, every land-based artwork I’ve made is in the American West (AZ, NM, OR, and WY).

When we first moved to Oregon’s Willamette Valley, I had to regularly get out of it either to the desert or the coast. I needed, hell I still need, more space. The desert ignoring me, its “not giving a shit about me,” Edward Abbey says is its central spiritual lesson. The desert’s utter indifference, and what that means for my small life, enables me to ignore myself.

I’ve also experienced the desert as a space where humans go as David Jasper wrote, “to encounter themselves, their demons, and their god.” This has been my experience too. Living for a year with several very human monks in New Mexico I learned a fair amount from primitive monastic Christianity and its connections to the desert. So there are at least three deserts at play for me, geographic, aesthetic and spiritual. There’s the outer formative landscape of my boyhood, desert as site for land art, and there’s the inner landscape of the desert.

Corpus, Playa Study #4 (process photo), 2017

Corpus, Playa Study #4 (process photo), 2017

Authority

As far back as I can remember, I’ve carried a fair amount of mistrust. Holden Caulfield and I, we were the ones who knew who all the goddamn phonies were. In terms of the Western Mythos I encountered; it only increased my suspicion of authority. While I traffic in it, I’m weary of high culture poisonous elitism, and I’ve never much liked preachers.

Of course, there’s a grit and loyalty and a code to friendship in the lore of the West. When someone wins me, they win me for life. I’ve got half a dozen friends I’d lie down in traffic for, and they’d do the same.

Pride and Shame

It wasn’t until living in a cross-cultural context for some time in Eastern Europe that I began to confront and negotiate my identity as a westerner. The “West is not any one thing, it is a tremendous collection of stories,” observed historian T.H. Watkins. “But no intelligent person can look at it without feeling a mix of both pride and shame.” As with reading the Bible, from both I receive a mixed inheritance that belongs to me for better and worse. I bear on some level ontological, historical and existential shame.

I came to recognize early and respect the boundary with primal/indigenous traditions. In terms of talking about the desert as place, course I’ve got a lot less skin in the game than first peoples do. I try to honor these folks by honoring our mutual otherness. I don’t wish to try to practice Native American spirituality or pretend to be an Indian. I struggle with the whoo-whoo Sedona and Santa Fe shit, tourists from all over sneaking into sweat lodges for quickie transformation.

Quite a few of my dialogue-based poems are particularly influenced by the way some folks (mostly white men) still talk in the West, an ecotone between old and new. It’s got to do with pace, understatement and directness. There is something laconic and patterned in the code of speech. And I can hear between and underneath the men talking both pride and shame. This is probably because I’ve got a double measure of both myself.

Culture

I grew up looking for coyote carcasses, walking desert washes and watching Clint Eastwood movies with my dad. Most of the furniture in my boyhood home was mission style aesthetic, stuff my father made out of pine with a likeness to what we saw in those Sergio Leone movies. There’s an uncle I had for a while before he went to prison who embodied a lot of the cultural trappings of the New West, handlebar mustache, Louis Lamour paperbacks, Camaro, cigarettes and R.C. Cola when he wasn’t drinking beer. And there’s a couple of older guys I’ve hunted with on the Mongolian Rim. One of them grew up a warden’s son in Florence, Arizona. When he was six, the Power brothers made him chaps and a holster. And I just don’t think I’ll ever grow tired of Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy.

And I’ve known violent brutal men who do equally violent and brutal work. Short-term and careless. And I’m thinking of William Kittredge who wrote, “There is in all of us an ache to care for the world….What I am looking for, at least so I tell myself, is a set of stories to inhabit, all I can know, a place to care about.”

When my wife got pregnant, I got lucky. While she grew up in France, in grad school in Tempe she got a feeling for the desert. From our damp dark, rain forest basement in Oregon, all she wanted to do for six months was eat saltine crackers and watch Westerns so she could see that sun and big sky and maybe some of that myth of redemptive violence. I’ve been reading McMurtry to my son, giving him the mythos. And he’s taken it—loves horses. In fact, he just read “Deadman’s Walk” cover to cover to earn himself a fancy French jackknife.

………………..

TCR: So you’re a dual artist, recently in the last few years taking up poetry writing to complement sculpture and land art installation and other visual and conceptual forms. How did this come about? Why do you think you needed language to branch out to as a medium?

CG: Well, it’s the second antler.

And a big part of the answer to your question is pragmatic. When we moved to Oregon almost a decade ago, choosing time and pace over money, I didn’t find much here in the immediate neighborhood or at the nearby college in terms of contemporary art practice. I found professional opportunities in Portland, Salem, Corvallis and Bend. I did an artist residency at Caldera. The Ford Foundation and Oregon Arts Council have been significant in supporting my work. What I did find in my immediate neighborhood was a motley crew of poets who, to varying degrees, are committed to writing, revising, and generally discussing poetry.

Around this time, an older sculptor friend of mine was talking about the need for serious artist-practitioners. The kind of folks who give a big chunk of their life to their art, even choosing against other kinds of work, to find more humane ways to sustain their practices. I’d always been something of a reader, I’d played with creative writing a bit in grad school. We had our first child, which limited my practice in significant ways, so I branched out into narrative poetry as a medium (antler tine). I really gave myself to making poems and getting them to final form. Doing this, I realized, enabled me to keep up with my artist colleagues in other parts of the state, country and in Europe. I could chase down grants and residencies and all the while sustain in the day to day domestic life, a writing practice.

Last year while finishing my MDiv, the Covid shit show landed. Suddenly going into prisons and hospitals doing chaplaincy stuff wasn’t so viable. So instead I’m putting together a theopoetic manuscript of my poems. That is, I’m trying to think about writing and poetry theologically. What does it really mean to release words into the world? What’s the risk, the responsibility? How does one do it with cross cultural competence, with a prophetic witness that doesn’t collapse easily into obvious categories? How does poetry allow us to steward mystery? So the ecotone between poetry and religion, for me, is porous.

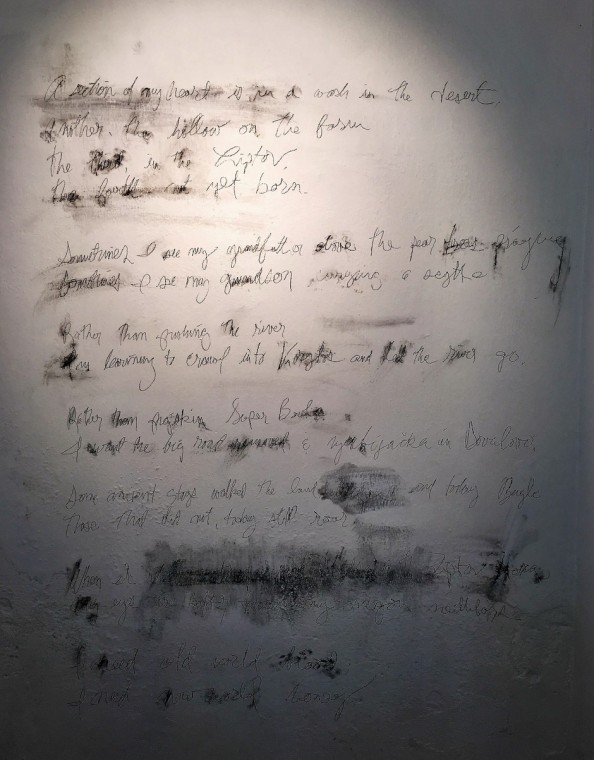

Ecotone Study #2 (wall text-drawing), Liptov, 2016

Ecotone Study #2 (wall text-drawing), Liptov, 2016

…………………………….

TCR: Second question to follow this one above: you published some prose poem and dialogue poems in the previous issue of Triggerfish (Issue #24: 45 miles west of Pittsburgh, and following, It’s mean cold). I have had the great pleasure of reading and working a bit with you on your full length manuscript of poems, and the title is Honey Wine and the metaphor and recurring motif is bee, hive, honey, and wine. Bees also play a time in your visual art. Would you like to tell us a little about what you’re up to through all this? The metaphor, the ambitious book and how these figures relate to you and all tie into your project autobiographically and spiritually?

CG: Yeah I am presently at work on a manuscript grounded in ecotones of content and form. The title and core symbol is Honey Wine. Honey for me over the last decade has been a stand-in for an excess surplus sweetness available in this life. Both a grace and a collaborative work. In my community-based projects, I’ve started thinking about my role as beekeeper, creating minimal conditions and structure to enable a mutual win/win. Not robbing the bees, but not going home without honey. Wine is a symbol of booze as well as blood. It ties to celebration as well as sacrifice, inheritance. Blood is life and in wine is truth they say.

One section in the manuscript “Old World” is a group of pieces, mostly line and prose poems, about the mixed blessing of ancestry. Specifically, my inheritance from the old world—the Slavic remnant I carry in my body that is both gift and liability, shame and pride. These poems try to get at some of the grit and lore witnessing to a harder and truer world than the one I was born into. “New World” is a series of dialogue-based poems situated mostly in the American West. Dialogue itself is a kind of ecotone (a transitional zone) sometimes making a third thing. This series follows a pattern of being titled after a place (a city/state) accompanied with a parenthetical scene, a brief description of setting 1-3 pages in length. They’ve been drawn from life as I’ve lived it, but they are not bound to it. I’m mostly after things tender, terse and gritty in the cultural terrains of urban and rural, folk and elite, animal and human.

The section “Foul-Mouthed Pilgrim” includes poems (prose, line and haibun) that mark my journey from boyhood, losing innocence before I knew I had it, to confessional poems and end with some poems about my son’s boyhood.

“The Fertile Dark,” I’d like to think is a prose poem, or perhaps poetic prose in 15 sections/pages that follows the story of a boyhood friend who’s spending the remainder of his life in prison. It includes the twin narrative of my own life unfolding, and may say as much about me as him.

My Imagined Reader

Jimmy Buffet’s got that lyric in one of his songs before the beach, “God would ride a bus so he could be with us.” Ideally, who I’m writing for is the folks who get assigned my middle seat near the lavatory after I deboard the bargain airline, or I finally get off the Greyhound bus and have accidentally left a bundle of papers on the seat. Bored folks flip through the way they might an airline magazine and something catches. They grin, shift in their seat and lean in. Then, less bored, they read on, and ‘Oh shit’, it holds their attention. They take it home. Maybe even try it out on a pal. I’d like to think this because of:

Form

Sure it’s poetry (we know that) but quite a few of them don’t look like poems in that modest plain prose form – blocks of text that hold story. My intention is that they be neither populous bubble gum, nor elitist and esoteric.

Content

There’s a nameless something having to do with life as it is lived, with human stuff. My sensibility is more akin to the wisdom tradition in the Bible, books like Ecclesiastes and Job that starts from below, with anthropos as opposed to theos. Or art that answers to life and life that answers to art (Bahktin). Maybe my ideal reader has a cousin, nephew, father or neighbor who has said stuff like is being said in these poems. Maybe my work reminds them of the farm, or a pretty good patch of land that got lost in their family, and they haven’t quite made peace with it either. Or something resonates with them in the poems about things going to hell, a tragic something–dogs gone feral, the earth being sick, why they stopped going to church… and yet.

So I see my audience largely as folk, perhaps uneducated, but by no means stupid people. People with an inner life who’ve had some loss, bad luck. Who’ve brushed up a time or two against mystery and aren’t dead yet. Who have their own stories to be sure, but who just haven’t written them down. Where they immigrated from and nostalgia and desire to keep some kind of continuity with it. People with “human faith” who at times may have even felt at home in this world. Who know what courage and horseshit is when it’s under their nose. Folks of various ages, but inevitably a portion of men who’ve played by some stupid codes and are reckoning with half their life being over. For whom being naïve once, was enough. Probably no longer certified insiders but more outsiders—former athletes doing landscaping, failed preachers, a few divorced adjuncts and dudes too fat to hunt anymore. And perhaps a portion of boy-men who respond to the physicality, animality and tenderness that I seek to witness to in my poetry. It offers a viable image that on their best day they want to live toward. I don’t ask for too much worthiness from my reader. While perhaps naïve, I like the idea of offering my poems to people who don’t read poetry.

But I don’t want to think my work is directed at half the human race. I want it to hold for anyone (though I recognize it is pretty American and heteronormative) who has a body that is aging, that at least wants to value labor and work and hasn’t quit on the longing to growing old and wise.

I am not consciously writing to men— privileged, white and violent. Or any other color. But if I was, they’d probably be privileged and white and plenty violent. I am not consciously writing to women. There’s stuff in the work about masculine gender constructions to be sure. Of course gender is its own kind of ecotone.

The practical, or most immediate audience for this work is other artists. People who read cross-genre, experimental, nature/environmental prose poetry. The folks who come to my art exhibitions and have attended my readings. The folks who buy my work and jury grants. Some of the folks I teach with. Less immediate perhaps, folks who are generally are interested in place, particularly the American West. A few misc. people who I’ve sat in silent worship with, lifted weights with, and men I’ve skidded logs out of the forest with. And maybe a few folks who live off the map, outside the center, who see their neighborhood represented in the collection. Hell, I’d like to try and do readings (post Covid) with wine and cheese at bookstores as well as readings in prisons. I’d like to think the work could stand up in both contexts.

I’m curious how poetry can happen in my home with others marking the seasons, sitting on that cantina couch in my silly little suburban backyard. And in everyday lived life with guys I do work with in shops, garages, trucks, fishing docks, bars, in the back country in front of a fire. I’m as interested in poetry as an artifact on a page in a book, as an event that happens in a landscape, that happens outside of the center. Art that jacks with life in a good way.

And yet, I want my poems, crude but well-built and sturdy, to hold up with poetry people. If I’m honest, I want my cake and eat it too. I want two honeydews. I’d be delighted if Garrison Keillor, or Carolyn Forché read one of my poems and said “Damn.”

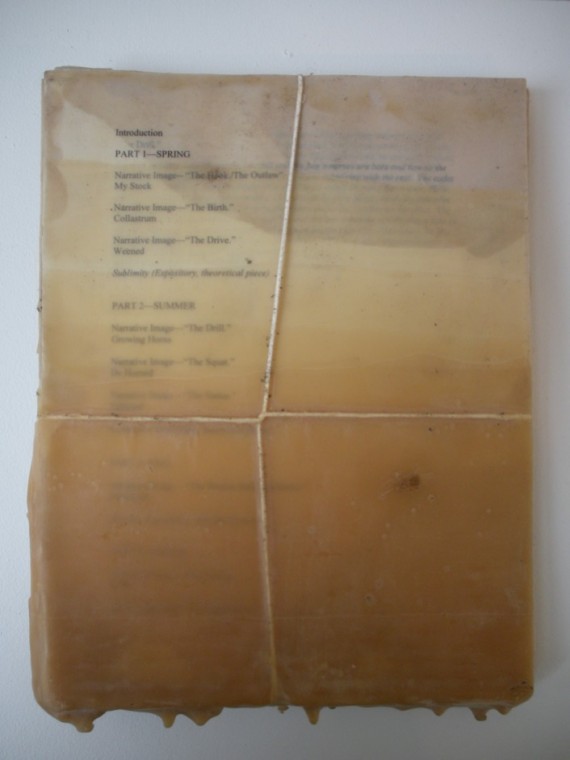

Manuscript (beeswax, wick) 2012

Manuscript (beeswax, wick) 2012

…………………………….

TCR: So, after you found out that I worked and wrote about my experiences at a landfill, you mentioned how great it would be if I took the work and read it aloud, onsite, to the landfill. Not to an audience, but to the place. Recently as we think and talk about doing collaborative readings during Covid, you brought up reading a poem to the empty room, before anyone shows up. You do these installations out in the landscape far from museums and don’t seem to think it’s necessary for anyone to see or visit them directly. What is going on here? Who or what is the audience? Who or what would be read to out in my workplace? Is it that the artist is changed and affected, or some hidden audience? What is the thinking here—I know this is key to understanding your art and practice, and your spirituality. I am scratching my head. Can you explain?

I wasn’t envisioning you going out to the landfill and speaking your poems into the air. Shit, I get giddy thinking how merciless your work buddies would be if they caught you out there doing a private reading. I was envisioning you out there with a second person with a camera documenting you reading your work in that context. Hell, I’d love to see a video clip of you speaking your poems in that particular place. The documentation and the digital artifact is a big deal in land-based art. Collectors and museums buy the documentation.

For starters, I think your question is getting at something about how I think about place. There are some places for me that constitute la carencia, the place in the bull ring where the bull returns for grounding, where character is drawn, as well as resistance and taking one’s stand. There are particular listenings available to me in particular places that are not available in any other geography. For example, walking a dry desert wash, our little family farm – its hills, hollow, creek, orchard and barn, and Slovakia’s Liptov villages and forests— Ticha Dolina (Quiet Valley) in the Carpathian Mountains. These are the places I repeatedly return.

And there are things to listen to here in what my novelist buddy in New Mexico calls the nursery. You can hear stuff at end of the Oregon trail. While it’s just a bit clannish, more suitable for homesteaders than pilgrims, it’s a place where I started my family and I can learn a lot from it.

I think your question may also be getting at art as an aesthetic intuition of the religious. There is a porous boundary between poetry and ritual/prayer. I am thinking of that passage in Cormac Macarthy’s “The Road”:

The boy sat tottering. The man watched him that he not topple into the

flames. He kicked holes in the sand for the boy’s hips and shoulders where

he would sleep and he sat holding him while he tousled his hair before the

fire to dry it. All of this like some ancient anointing. So be it. Evoke

the forms. Where you’ve nothing else construct ceremonies out of the air

and breathe upon them.

Maybe poetry is religion pursued by another means? We are animals to be sure but we are also liturgical creatures. One of my former teachers, Dan Siedell wrote a lot about how an artistic practice recognizes this.

So sure, speaking a poem aloud can be a way of consecrating space, a way of dwelling in the world non-literally, living on more than one level.

Ritual in the Dark, Nicarry Chapel, 2012

Ritual in the Dark, Nicarry Chapel, 2012

…………………………….

TCR: Why is your work so ugly, harsh and brutal? It isn’t only that of course but as a parting shot, let me throw that at you…Actually let me modify that. There does seem to be an ugliness and harshness ( austere beauty at best) in the installations and sculpture, but I notice the poems have this quality as well but also often tempered with tenderness and warmth. Also this interview hints at it. So is it when you work with language those other qualities can be present but is less so in the visual art?…The more I think about this, there is definitely tenderness in some of the drawings of deer and bees, but harshness too…

CG: One evening I sat Beauty on my knee; and I found her bitter, and I injured her.

—Rimbaud, 1873

The fairies dance and Christ is nailed to the cross.

—Alfred North Whitehead

When I was in college, an extended family member told me: “If you want to understand our family, watch this movie.” She gave me the “Deer Hunter.” Pennsylvania steel mill, Slavic culture, soldiering, solidarity, aggression and intimacy, church music paired with the hunt.

The contrast between the sacred and desecration, brutality and tenderness is stark.

9 Korytos, (Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia) 2015

9 Korytos, (Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia) 2015

Broadly speaking, we’ve got the two traditions: Platonic and Aristotelian, realist versus idealist, talking about what is, and what ought be. An artist I think, has got to feel the world without cheating. And also see the world with soft eyes.

I’ve seen beauty damaged. And I’ve both wounded and been wounded by beauty. My graduate thesis “Sacred Offense” grounded in the austere beauty of deserts was about how art and beauty have the power to empty, to decenter and displace. I’m interested in what Yeats called, “a terrible beauty.” Beyond the self-referential and sentimental, art, I think, has got to reckon with the tragic dimensions of this life. I’d like to think my work as a whole holds the tension between the two.

TCR: Thanks man! More about Craig’s work can be found here: http://craiggoodworthart.squarespace.com/

Jelen and Other Drawings, 2011

Jelen and Other Drawings, 2011