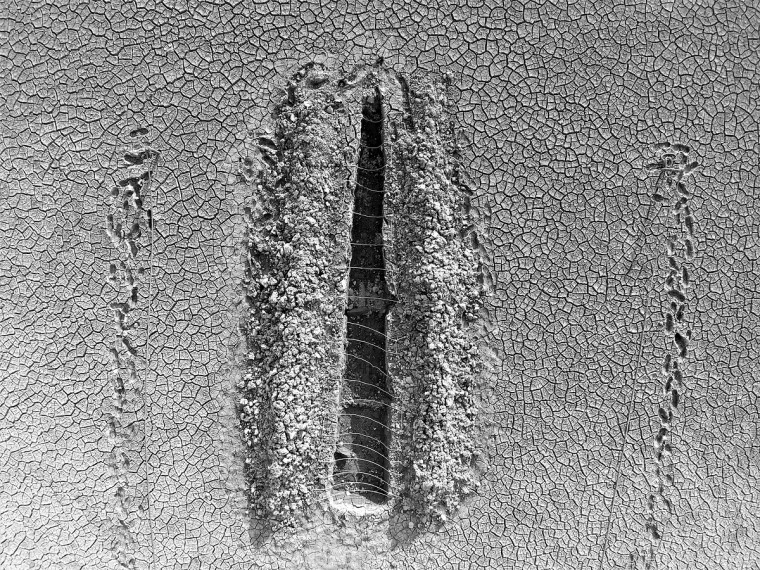

Craig Goodworth, Corpus, Playa Study #4, 2017

Craig Goodworth, Corpus, Playa Study #4, 2017

Cain

Hitching after my shift one bitter night I got in when he offered. The man had a force field around him, cigarette smoke in his clothes, a kind of fierce pulse. He knew where I lived. I knew him by name. I sensed right away he liked me. Merle Haggard on the radio, a six-pack on the floor, Cain in the back seat.

The dog, he claimed, was half wolf. He’d found it in the shed, shivering and starving. Could have shot it but instead named it, said he liked having another mongrel around, one scrappy bastard to another.

He drove through our wasted town, its one bar closing, past the high school we’d both hated, down county and gravel roads flat and T-squared. Everything’s scarred, I said. 2:00 a.m. and we were both wide awake.

He stopped at the cemetery. I showed him my mother’s grave. Snow had drifted over the writing, Jesus called her home. Orion straddled that deep black sky, the tip of his sword glittering, dogs faithful at his feet. Our breath without words, small clouds that vanished.

Better get you back, he said, and I wondered what a real home should feel like.

_________________________

Debra Kaufman

Review by Dave Mehler

I think this is a perfect or nearly perfect, but modest, prose poem. The loaded title is prevented from being heavy-handed because it is the name of a dog (that is half-wolf), but it is not insignificant that the dog is the only character named (and half wild and half tame) and the man and woman as main characters remain unnamed. We get pulled through the brief narrative with all the marvelously specific details: the woman is spared walking home on the bitter night by hitching a ride after a long minimum-wage shift; it is snowing, two in the morning, Merle Haggard is on the radio, the fact that woman (rider) and man (driver) went to the same high school and hated it which also serves to place them as about the same age but doesn’t have to tell us that, and we are told the driver likes the rider and the rider knows it. It isn’t explained what the man is doing driving around at 2 am with his dog in the backseat and a six-pack on the floor, and for that matter we don’t know what kind of job she works. 2:00 is when bars close, but she doesn’t work for that one bar that’s closing, so maybe it’s an all-night diner, or she’s a night clerk in a hotel? For some reason he’s out too, driving home, maybe a customer in the diner? The speaker seems to feel safe with the man and whatever might develop enough to stop at the cemetery and visit her mother’s grave on the way home, which allows for the penultimate paragraph to take a metaphysical turn, archetypally, with this stop at the cemetery, an inscription on the speaker’s mother’s grave, looking up at the constellation in the sky (source of spirit and awe), noting an ancient hero’s glittering sword with faithful dogs commemorated by stars, and breath like pneuma, without words. This could be a shift that’s too emblematic, but it’s barely noticeable because of the context it’s slipped into and actually quite believable, just odd. The speaker has a two word bit of dialogue offered: everything’s scarred. The man responds finally with four words, ‘Better get you back.’ Ending on a note like this, and I wondered what a real home should feel like, after all the preceding along with the title can’t help but reinforce a biblical frame of reference in which the speaker and her good Samaritan and the gravestone’s inscription telling us buried beneath the snow, Jesus called her home (which the speaker’s last sentence is responding to), and her earlier observation that everything’s scarred all add up to one thing: we are homeless exiles here, and under a curse. A home once existed and maybe still exists out there somewhere for some, but we down here can no longer imagine what that might be like. The entry point back to paradise has been hidden and even if discovered is blocked and guarded by an angel with a flaming sword. The speaker’s mother found it according to the stone, but that involves Jesus, and dying. I know that Debra Kaufman hails from North Carolina, but I feel like we’ve entered Cormac McCarthy country, or maybe more appropriately the Christ-haunted South of Flannery O’Connor–but I get McCarthy’s West even more. One last thing about the style, I appreciate that Kaufman rather than a block uses paragraph breaks to hearken us closer to a poem with line breaks: rather than a solid paragraph block we get 3, 2, 2, 2, 1.