Marilyn Higginson Profile and Interview | for Triggerfish | Dave Hegeman | June 2019

I first discovered Marilyn Higginson’s wonderfully crafted landscape paintings at an exhibit of her work at Art Elements Gallery in December, 2013. (It might have been even earlier, shortly after the gallery opened in 2010.) Her work resonated with me immediately, keenly capturing the soul of the farm fields, orchards, savannahs and wooded, rolling hills of the region where Polk and Yamhill counties intersect. I had traversed this area countless times. They were so true to the land of these parts — but in a fresh, unique way. Higginson’s affinity for seasonal changes, certain times of day — even the weather — is readily apparent. It should be pointed out that she gives the same attentive treatment to the landscapes of eastern Oregon and the coast.

There are at least two things worth noting about Higginson’s landscape canvases. First, is the color: subtle, ever so carefully modulated colors. There can be no doubt that she expends a great deal of effort into finding just the right value and hue. The result is a powerful sense of mood and visual cohesiveness. Second, is the architectonic quality of Higginson’s landscapes. (This quality extends even to her other works, including ceramic vessels, sculpture, and — recently presented last fall — a series of abstract paintings evoking the basalt rock formations she has encountered in Oregon.) When I look at her landscapes, I can feel the bones and rhythms, and the vast, variegated sweep of the land. She almost makes it look easy. But this belies the extraordinary care she invests to get the structure of the image — balance and composition — just right. Every element has its place.

On a recent Saturday afternoon in June, Marilyn Higginson graciously agreed to meet me at Art Elements for an interview. Special thanks goes to gallery staffers Sarah Askins and Sarah Moore for their help, including pulling some of her paintings out of storage so we could refer to them as we talked.

✶✶✶

Marilyn Higginson, Fragment Series #7, Oil on Wrapped Canvas, 24″ X 24″

Marilyn Higginson, Fragment Series #7, Oil on Wrapped Canvas, 24″ X 24″

Thinking about your landscape paintings, your ceramic pieces including the one before us [Kare Sansui – a coffee table incorporating glass, welded metal and white clay evoking dry creek beds found in Japanese gardens], as well as your recent abstract works, what do you think is the common thread between all of them?

Well, its nature. In a word. It almost sounds silly: I am in love with nature.

I don’t care much about cities. I don’t think there is a painting I have that has building in it…well there is one… but it is very small.

I just love the color and the texture — or the lack of color. The color that’s not blinding. The piece over there by Romona [Youngquist, across the room] is quite bright. I enjoy Romona’s work, but I don’t go there, normally. I use color more subtly than a lot of artists. I don’t think you have to have it in your face…color. It’s there in nature but I tend to tone things down a bit, I think.

You mentioned before that you capture certain times of day where the colors are naturally more muted…

Well, yes. I think that noon is the most boring hour of the day. I like to work with the twilight ends. The light is leaving then, so you don’t get a lot of color on the retina. And it’s a challenge to lay that back, push it down as far as possible without losing the image. This piece here [Dawn at Nehalem Point] — the big place in front is Lazarus Island from Wheeler (just for your information on where that is) — the tendency is to want to make things lighter and brighter. And I then stand back, look at it and, well, that needs to go further down. So I want, almost, to have it not be there.

Marilyn Higginson, Dawn At Nehalem Point, Oil on Wrapped Canvas

Marilyn Higginson, Dawn At Nehalem Point, Oil on Wrapped Canvas

I thought of doing a series of paintings (and it could still happen) — paintings that you have to not look at [straight on] to see. That would be the fog pieces. Because when I am working on the blends in the sky that you see there [gesturing at Dawn], I’ll be at arm’s length, blending away, and I think well, I’ve got it. And when I step back and look at it — the painting’s here [holds up her hand] and I look here [slightly to the side] and it’s stripes. So I know that the portion of the eye — not that part you use to focus with — that part we use to see value and movement. And when I step back and look away, those parts of the retina are seeing the changes in value. So then I know that I have to go back in there and look at it with those [eye] cells and see that it is a complete, seamless gradation.

So these fog pieces — that I may or may not end up doing – if you would look directly at them there would imagery there that you would not necessarily see. And you would have to go around [Marilyn moves to the side and looks off to the side slightly]… to see what’s there.

So where do your landscape paintings start? Do they start with drawings? With photographs? From your memory? How do they evolve?

Well I collect a lot of photographic imagery to assist my memory. I bring my camera — or my phone — along. ‘I like that, I want to remember that’.

The Japanese say that we enhance nature by editing it. Everything you might recognize about a particular place in a painting of mine, like that one [motions to one of her paintings in the room]…it’s not like a photograph or a representation where every little tree is in its place. I don’t work like that.

Well I am sure that that is true of most landscape painters, even photo-realists make changes to the scene they are depicting…

Yes. Sure.

So compositionally, how are you building it?

Well, it is part of the editing [process].

So do you do the editing ahead of time, or work it out on the canvas?

It works out on the canvas, usually. As I am working I will see…that (whatever it is) it not working there, so I need to move this over here, or move that up, or cut off that line of trees right there…

Now this piece here [Corn Stubble] has a very calligraphic play of marks in the foreground…

Marilyn Higginson, Corn Stubble, Oil on Wrapped Canvas

Marilyn Higginson, Corn Stubble, Oil on Wrapped Canvas

Yes. I like to do that. It is just physically joyful to work with a calligraphic brush. Because some of the other areas are a little more fussy.

You mentioned the Japanese saying about editing. You refer to Japanese ideas and aesthetics frequently in your artist statements. What is your history of interaction with these ideas and writers? When did you first learn about these ideas? Have you traveled to Japan? Did you take classes or have a mentor for these ideas?

I really can’t remember when or where it began. I had a friend who owned an Asian arts/antiques shop. She had exquisite taste and always wonderful ceramics and furniture in her place. Another friend had lived in Japan and opened a gallery in Portland, with the work of Japanese artists and Americans living in Japan.

Many people have asked me where I studied in Japan, how long I lived there, assuming I have. Nope.

The aesthetic was always hovering, somehow, and I feel at home with it. I haven’t yet been to Japan, but may be going in the next few years.

As for a mentor, I haven’t had one, but I had the great privilege to meet Koichi Hara, the founder of Japonesque Gallery in San Francisco. I took a few pieces of sculpture there and we had a wonderful — and very enlightening — conversation. He liked my work and had some helpful things to say. I even sold a piece or two. The rest is having a sense of being on the right path.

I do admire the craftsmanship, the willingness to spend a great deal of time and experience to produce beauty.

Do you think there is an aspect of Japaneseness in your landscapes?

Yes. I think when they successfully communicate a mood of tranquility, peace, calm and are simple seeming, even when they are grand. Also, I’m not interested in putting forth my own personality. The paintings are about the subject, not about me. I am a messenger, only.

So when did you move out to the country [in Yamhill County], to this area rather than Portland — and you became more aware of the landscape?

I bought property in 1996 and waited a year or two for the excavation of the driveway and putting up the building. And [finally] there was a studio there.

I did a little landscape painting while I was there [in Portland]. But my work space was difficult. So when I moved out to the country I had more space– in my workspace — and the outside to draw from.

So that was a life transition for you artistically…

…well in every way. I could not bear to live in Portland now. I did not like the driving there, I did not like the density…I’ll go to places to get an urban fix and then I want to go home.

So earlier in your life did you spend a lot of time in nature? Was it always percolating in you?

Yes, always. My father was in forestry. He was at Cal [at the University of California forestry school] Berkeley literally when I was being born. When he graduated, the forestry department sent him to a place called Badger Well in Modoc County [in Northern California]. We lived in a log house and the nearest neighbor lived about a mile through the Ponderosa, and we were alone. I was a little kid. And it just stuck. They say that your life is sort of formed by the time you are five. So all of that, by age five, was nature, solitude…and the fear of snakes! [laughs]

Speaking of a larger work space, have you ever wanted to work really huge? Say 8 x 10 or even bigger?

Well, I like to be able to pick up my paintings, so 48 by 60, that’s my wingspan. I have worked larger than that, but rarely. The painting Alvord Dawn [now in the collection of A-Dec, Inc.] is about 90 inches wide, but I can carry it this way [by the narrow dimension].

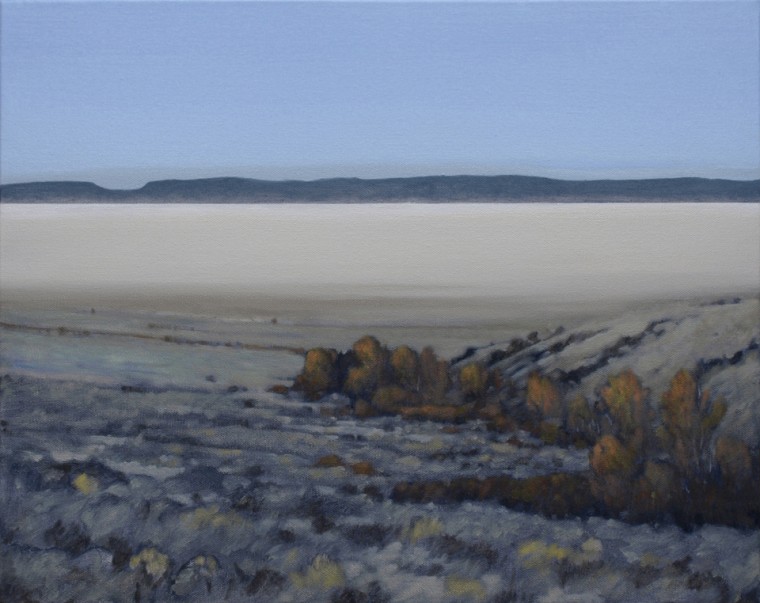

Marilyn Higginson, Alvord at Dawn, Oil on Wrapped Canvas, 41″ X 96″

Marilyn Higginson, Alvord at Dawn, Oil on Wrapped Canvas, 41″ X 96″

Who are some of your artist heroes? Do you look at a lot of other art?

Yes. I do. And like aspects of what they are doing. I think that somebody still alive would be Russell Chatham. I admire his work a great deal. When I was starting out doing the landscapes that I do now, having moved [to the country], I saw his work, and I went, ‘Wow, that’s how it’s done.’ Where you are ‘young’ at it, so to speak, an artist you admire…you think, ‘what would Russell do.’ But I am way beyond that now. I don’t look at his work to see what I should do. But when you are starting out, as a student or new to a medium, you look to other people’s work to see what inspires you, and then you go on from there, and work out your own ways of working — your own imagery.

Do you think about the viewer much when you are painting? Are there things about your paintings that you hope others notice and walk away with?

I am not articulate about it. I do the painting and leave the interpretation to the viewer. If I can get someone to stand and look at a painting and say, ‘I want to go…I want to be there. I want to walk through that landscape.’ Then I feel pretty successful.

Do you want them to think differently about color? Do you want people to notice the way that it is painted?

Yes. I told you earlier about the guy who said I didn’t use enough paint. One reason for that is that I don’t want…my paintings are not glossy. They’re rather dry — the surface. I don’t have a lot of texture in the brushwork, because every little brushstroke captures light and I want to be able to see the image — just the image — from wherever I’m standing, without having to edit out a bunch of little shiny things from brushstrokes. So I take great care to minimize the texture of doing the work, of the brush, because I want people to see the imagery…because a lot of my imagery is very subtle. I don’t want to fight with surface artifacts.

Well, yes. Looking at the paintings I have seen of yours, that is very evident…

I use the word “jacquard effect” sometimes. That’s what it is. If you paint this way [gestures up-down] and then you paint this way [gestures side-to-side] it looks like a different color, even if it’s the same paint on the same brush. And it’s because of the way the light hits it. So when I am doing these blends, I’m blending this way and that way and this way and that way [gestures in different directions]. But the final brushwork is just a very soft brush and straight across the canvas [side to side] without stopping, until I get it absolutely flat. Otherwise there will be — not changes of color — but changes in light hitting the canvas that will eliminate that seamless gradation.

So, are there some paintings you have done that you feel particularly good about? Paintings where you were ‘right there’ in terms of what you are trying to do artistically?

There are a few whole paintings, and then there are pieces of more. I’m fond of the lower third of this piece [Dawn at Nehalem Point].

I don’t know if I have an absolute favorite…Well there is one. But its at home, and it will always be at home. It’s a view of Alvord [Desert] from Pike Creek in the early evening. The sun is going down behind us over the Steens [Mountain]. So you’re getting a growing shadow. But across… the Alvord is just a very pale — yellowy-pinkish — with the last light. (I think that’s part of the title, Pike Creek — Last Light.) Part of it is that I really like the painting, and part of it is that that’s where I used to go with my father.

Marilyn Higginson, Autumn at Pike Creek, Oil on Wrapped Canvas

Marilyn Higginson, Autumn at Pike Creek, Oil on Wrapped Canvas

Did you used to camp there?

Yes.

So that painting must have a place within your soul…

It absolutely does. That puts me there. My father used to buy George Dickel (allegedly a bourbon!) and he used to drink that with his friend. So we brought that. And we’re sitting there doing that in that painting. Of course we are not actually in the painting…

The experience of being there is in the work…

Yes. And its a nice painting besides.

I like to say that I am happy when a painting reaches a point where it begins to paint itself. And I went to bed one night when I was working on that painting with a list of things I needed to solve and overnight (you know, people say, ‘sleep on it’)…I woke up and went into the studio and I checked them off. And that was the painting painting itself. When I’m just there holding the brush. All of the things that the painting wants are coming to me to do that.

It feels really nice. Because sometimes you struggle for a while. And I’ve had struggles with a painting where I get lost and I don’t know what my intentions were. I’m just lost. And I’ll hang it over there, out of the way but where I can see it if I want to. And sometimes a painting will hang over there for a year. And then I’ll go back to it.

I have a painting that’s at The Allison [a hotel in Newberg] now. It began in an entirely different season and time of day than it is now. But it took that long for me to be able to give up the original intention and go in some other direction [that worked]. (It’s in one of the elevator lobbies.) My favorite painting there is in the spa (on the wall at the end of the hall, November at Baskett Refuge).

Marilyn Higginson, November at Baskett Refuge, Oil on Wrapped Canvas

Marilyn Higginson, November at Baskett Refuge, Oil on Wrapped Canvas

What did you like about the painting in the Spa?

I think I discovered new ways of working with that painting. I like that it’s foggy, it’s moody, it’s misty. I learned a lot from making it. So if you’re there and see it, look at the brushwork. There is a lot in there that I use all the time.

You can find more of Marilyn Higginson’s work here: http://marilynhigginson.com/

or at ART Elements Gallery here: https://www.artelementsgallery.com/collections/marilyn-higginson