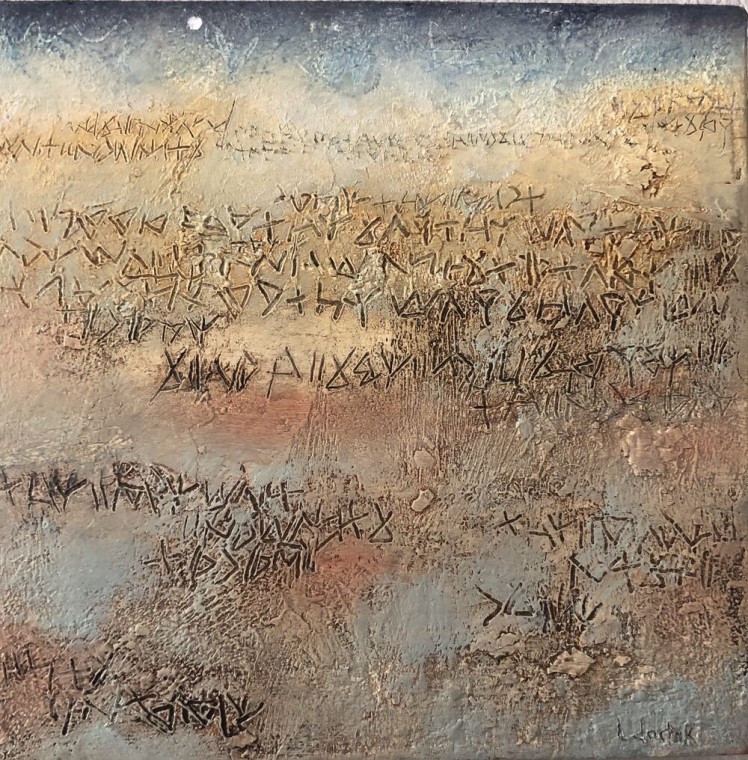

Laurie Doctor, Time and Night I, Oil on Wood, 5″ X 5″

Laurie Doctor, Time and Night I, Oil on Wood, 5″ X 5″

It’s mean cold

west of the Alleghenies. I’m eight years old and under a stack of blankets. Wake up boy, you wanna see somethin’ get born? my uncle says. Through frosted glass, I see the dim barn light. In the basement, he dresses me in blue coveralls and rubber boots, too big. I prayed this heifer would calve before the worst of the weather, he says. The shit and muck is hard as the creek that’s frozen over. I sit on a saddle blanket atop a couple of buckets and watch the labor. The cow, aloof, lurches, blinks slowly, and pushes the calf from her warm deep belly. You want to help her? When he tells me to, I tug on slick rubbery hooves. He takes a glove off and with hooked finger, unplugs the calf’s nostrils. The cow rocks to her front knees, stands up. Once past the shoulders, the calf spills warm, wet and steaming onto the straw. Welcome, my uncle says. I watch the cow sniff then lick her calf. What’s she eating? I ask. That’s afterbirth. Her eating it keeps the coyotes away. Straddling the knock-kneed calf, I dry the neck while he towels the belly. In the pre-dawn light it’s still pretty dark, and bitter cold.

middle-aged I wait

she tells me she just doesn’t feel

pregnant anymore

_________________________

Craig Goodworth

Review by Paul Jones

Goodworth is particularly attracted to dialogue and the mixed genres, feeling free to adroitly drop prose into the texture of his verse. But I want to instead notice his haibun, “It’s a mean cold,” which draws on an eight year old’s memory of calving in winter (poor planning on the part of the farmer? We mate to calf in spring in NC). The messy miracle of new life and the labor that brings that life from womb to world is well described. Then in the haiku, a poignant moment of loss or of another birth to which he has been a part.

Review by Dennis Hinrichsen

“It’s mean cold,” the last poem in this very tight sequence of three poems, picks up on the heifer calving moment in the previous poem and extends it here. So many things to admire. The way the title crashes into the first line of poem and resonates literally and metaphorically. I admire again the real world detail in this poem. And then the formal gesture—the haibun done American Roots style. Very nice. What a smart and brave move here to set that dense prose stanza against the leap in the closing haiku that completes the yin yang dynamic at the core of this poem. Love how each one of these poems stands alone yet when read in sequence form a powerfully linked argument.

Review by Steve Hatfield (This review began as a single review but generated into a conversation, amongst Hatfield, the editor, and Craig Goodworth—which is a little different, but I thought worthwhile and interesting enough to reproduce here—Dave Mehler)

Here is a dandy (sharply composed) demonstration of juxtaposition and ambiguity as literary ammo. The former is obvious at a glance—a narrative paragraph and what’s that—haiku? Okay, close enough. The ambiguity resounds with each reading.

Apparently an abortion has taken place, and apparently the poem is the poet-speaker’s response not only to the fact of the abortion but to the female’s attitude about it. So what’s on his mind? His present-tense memory of a cow that gave birth in awful conditions, whose first responsibility after delivery was the calf’s protection, provides a vivid backdrop for his experience years later of a human mother-to-be who said no to the whole thing, and who seems to be as pragmatic about her decision as if being thirsty she had taken a drink of water. Does the speaker condemn her? The bitter cold on the night of the calf’s wet and steaming birth surely is indicated by the “mean” in the title, but since “mean” can also describe a certain attitude about abortion in general, not to mention one’s decision to have one, the speaker does indeed appear to portray the woman in negative light. (Is she the “it” of the title, too? Has the woman sacrificed her humanity with her decision?)

But the poem is ambiguous. An equally valid reading is that the speaker’s memory of that brittle morning years ago provides the contrast by which the speaker so concisely and clearly depicts the woman’s sovereignty over her own life. She is no mere animal, controlled by her instincts, dependent on male assistance (or approval). She made her decision, and right now, if you must know—you, who has no idea—she just doesn’t feel pregnant anymore. (What strength that little word “just” acquires as she uses it here!) Now the title uses “mean” the way some slang employs “bad” or “ill”—as in, “it’s mean cold” how that woman answers men who’d question what she does with her reproductive power. Read this way, one can almost hear her saying after that last written word, “so eff off!”

The poem’s power is its ambiguity. If the speaker had come down on one side or the other, well, ick. By leaving the poem ambiguous, the poet allows the reader to experience the debate without being told how to feel or being manipulated into feeling one way or another, perhaps without at first even realizing he’s getting both sides. That isn’t everything this poem has going on, but for now, it’s enough…

TCR: Steve, would your review change substantially if you granted the possibility that the event in the haiku portion might be a miscarriage and not an abortion? Also the haibun (or combination of the prose poem and haiku) has been around at least as long as the 17th century in Japan, a form, if not invented by Matsuo Basho, at least its most famous practitioner…

Review by Steve Hatfield, Part Two

Having never before encountered the oriental poetic form haibun, to which this poem (I have learned) adheres, I can only offer my take on the poem as it strikes me. Its quality as a haibun in particular I leave to others. So,

the morning the cow gives birth is bitterly cold. Is it mean cold? In the vernacular, sure, it’s mean cold. The concluding haiku must relate to that mean cold, but how? It can’t be literally. But those last three lines sure feel cold. What’s the connection? The answer is the poem.

The cow fulfills her biological function, despite the cold. Uncle would have preferred a time before the bad weather, but what say does he have (or does the cow have) in such things? In the haiku, the woman, who apparently has not successfully “calved” a babe, is indirectly quoted—she doesn’t feel (in fact, she isn’t) pregnant anymore.

Whatever has happened to her must catch up the cold the morning of the calf’s birth and the mean in the title, and I can think of a couple of experiences she might have had that do that. Leaving the matter ambiguous, however, seems advisable, because the poem doesn’t appear to be about her specific experience so much as it is about what her experience together with the cow’s experience suggest about the only mystery in life that rivals death—pregnancy and birth, in this case from the poet-speaker’s male point of view.

As a boy, the speaker is roused for an up-close-and-personal experience of birth. It’s something—memorable—but at the end “it’s still pretty dark” which by the poem’s end we realize speaks to his boyish apprehension of the mystery. The cold that morning, too, can be read figuratively—it’s cold of the mystery to have moved in the cow that morning, and what the cow pulled off at the mystery’s command that morning was cold, too.

As a man, the speaker encounters an almost-delivery from a distance—the best he can do is wait for news, and when the news comes, it comes coldly, and it is cold news. No afterbirth to eat this time; the coyotes, man, whatever they were, however they did it, ate that baby.

His adult mind links this cold moment to the morning years ago when things went “right.” What went “wrong” this time speaks to the mean in the title—is the mystery of pregnancy and birth mean cold fundamentally, like a computer program or a mechanical function? The title says IT’S mean cold, so yeah, maybe it is, at least in the poet-speaker’s mind: what females go through is mean cold, when it works and especially when it doesn’t. Certainly the woman’s indirect and “cold” summation of her experience at the end supports that reading.

Coming to a conclusion about this poem, however, no doubt does the poem (as it would do to many good poems) a disservice. All that really needs to be said about this poem is that it makes the reader feel helpless at the end, helpless and humbled in the presence of something beyond his control that is mean and cold.

Steve Follows up one last time

You know, the more I thought about the poem and what I was doing with it, the stronger it struck me that landing in it one way or another was doing wrong by it. That is, the feel of it suggests to me a Chinese painting of mountains and lakes and such—the space in it invites one to enter into it and to experience therein what?—his own mind, maybe? Of course, I’ve never actually had that kind of experience while looking at a Chinese painting, but as I understand that art, such an experience is available to any viewer who accepts the invitation. This poem, however—maybe it’s the distance between the two parts of it—I walked into it and in trying to make sense of what I was feeling I landed on abortion as the explanation. But see, in China world, explanation isn’t what it’s about. I get that, but my sensibility is orientated in a western direction—what’s a poor boy to do?

So when you advised me to think about a miscarriage, I thought well, of course—that made sense and was more poetic, in its way, than a poetic statement about abortion. But it isn’t just about a miscarriage specifically any more than it is just about an abortion specifically, yeah? What comes to mind is MacLeish’s admonition that a poem should not mean, but be—which always made me wonder what there was to appreciate about a poem that didn’t mean anything—and the admonition English teachers used to receive and share out (do they still?) that the reader makes his own meaning—which I always thought excused a lot of horseshit interpretations of poems, etc. Point is, half of me wants to pick up this poem and shake it and the other half of me wants to just back away and let it be all inscrutable as a geisha’s smile, which means at each reading, one half of me leaves dissatisfied. Is that the mark of a good poem or no? I don’t know. But I sure like talking about it.

Craig Goodworth Responds:

While this haibun is not strictly autobiographical or self-referential, it is actual. That is, it seeks to reckon with life as it is lived. I make art that answers to life. And on some level, I live a life that answers to art. It’s Mean Cold is a made thing, and that it has opened up aesthetic and moral wonderings pleases me. It would seem this little piece of art has been ambitious.

What is the nature of nature? Over two decades ago I read Crane:

A man said to the universe:

“Sir I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

A sense of obligation.”

—Stephen Crane (1871-1900) from War Is Kind (1899)

I like that my reviewer correctly senses the naturalism in this piece that has spooked my work for years. And he is on to something about not ignoring the coyotes—those who smell afterbirth and come rushing in. They matter. Exactly how and why, this poem doesn’t answer. But they are acknowledged and necessarily remain in the landscape of the poem, crouched behind the sassafras in the blind spot of the speaker and perhaps the reader. I am thinking of theologian John Cobb who said, “Life eats life.”

In terms of form, I’ve been interested in hybridized stuff for a while now. The Japanese Haibun that holds together:

prose / haiku

And in this poem my effort to hold

boyhood / aging

male midwife / mean (or indifferent) naturalism

It’s Mean Cold bears witness to both what Trappist monk Thomas Merton called Point Vierge and is a kind of requiem.