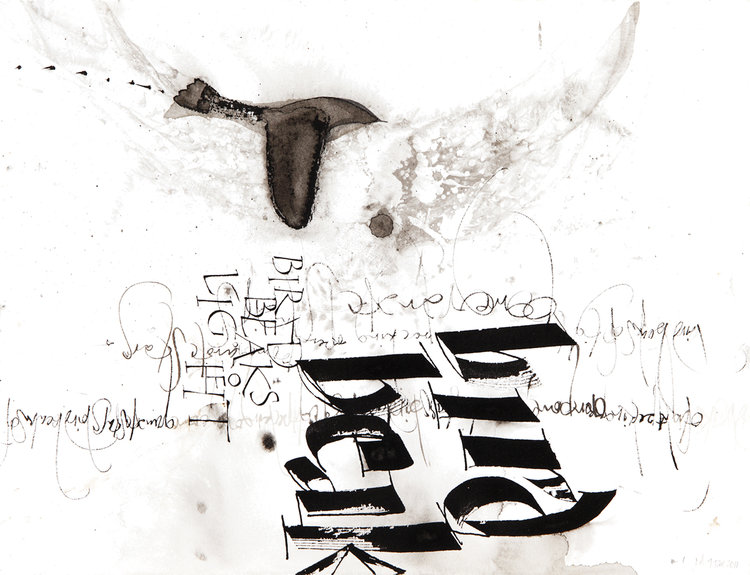

Laurie Doctor, Bird Beaks of Light

Laurie Doctor, Bird Beaks of Light

Collage

There is a simple truth which one can learn only through suffering: in war not victories are blessed but defeats. Governments need victories and people need defeats. Victory gives rise to the desire for more victories. But after a defeat it is freedom that men desire—and usually attain. A people needs defeat just as an individual needs suffering and misfortune: they compel the deepening of the inner life and generate a spiritual upsurge. [pg 272]

—Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, from The Gulag Archipelago

At the end of the workday there were corpses left on the work site. The snow powdered their faces. One of them was hunched over beneath an overturned wheelbarrow, he had hidden his hands in his sleeves and frozen to death in that position. Someone had frozen with his head bent down between his knees. Two were frozen back to back leaning against each other. They were peasant lads and the best workers one could possibly imagine. They were sent to the canal in tens of thousands at a time, and the authorities tried to work things out so that no one got to the same subcamp as his father; they tried to break up families. And right off they gave them norms of shingle and boulders that you’d be unable to fulfill even in summer. No one was able to teach them anything, to warn them; and in their village simplicity they gave all their strength to their work and weakened very swiftly and then froze to death, embracing in pairs. At night the sledges went out and collected them. The drivers threw the corpses into the sledges with a dull clonk.

And in the summer bones remained from corpses which had not been removed in time, and together with the shingle they got into the concrete mixer. And in this way they got into the concrete of the last lock at the city of Belomorsk and will be preserved there forever. [pg 99]

—Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, from The Gulag Archipelago Two

I do believe that poetry makes better people. How come we’re not allowed to say this? Nobody says this. There is a great poet, I won’t mention his name, who said, ‘Poetry isn’t therapy.’ I think it is, and in fact, when I read his poems, I felt they saved my life. Am I stupid? Am I one of those idiots who goes around saying that poetry saved my life? His poems, I can say this, saved my life. And I bet they saved his life.

—Li-Young Lee, from The Subject is Silence, an interview/essay included in A God in the House: Poets Talk About Faith, edited by Ilya Kaminsky and Katherine Towler

The stars report a vast consequence

our human moment joins.

Or is it all the dark

around them speaking?

—Li-Young Lee, from The Bridge (Book of My Nights)

And of all the rooms in my childhood,

God was the largest

and most empty.

Of all my playmates,

my buried brother was the quietest,

never giving away my hiding place

—Li-Young Lee, from Stations of the Sea (Book of My Nights)

And the sun, our star, that vast office

we sit inside while the birds lend their church

sown in the air, realized in a body uttering

windows, growing rafters, couching seeds.

—Li-Young Lee, from My Father’s House (Book of My Nights)

Two breadvans pass in the night

and a shipment of mustard arrives on schedule.

—Michael Earl Craig, from Commerce (Can You Relax in my House)

The trees aren’t intentionally bad.

—Michael Earl Craig, from Springtime Hits the Pioneer Valley (Can You Relax in my House)

A caterpillar takes a breather.

—Michael Earl Craig, from The Au Pair, on Barbiturates (Can You Relax in my House)

By the light of the lantern brought on deck to examine the sounding-rod I caught a glimpse of their weary, serious faces. We pumped all the four hours. We pumped all night, all day, all the week—watch and watch. She was working herself loose, and leaked badly—not enough to drown us at once, but enough to kill us with the work at the pumps. And while we pumped the ship was going from us piecemeal: the bulwarks went, the stanchions were torn out, the ventilators smashed, the cabin-door burst in. There was not a dry spot in the ship. She was being gutted bit by bit. The long-boat changed, as if by magic, into matchwood where she stood in her gripes. I had lashed her myself, and was rather proud of my handiwork, which had withstood so long the malice of the sea. And we pumped. And there was no break in the weather. The sea was white like a sheet of foam, like a caldron of boiling milk; there was not a break in the clouds, no—not the size of a man’s hand—no, not for so much as ten seconds. There was for us no sky, there were for us no stars, no sun, no universe—nothing but angry clouds and an infuriated sea. We pumped watch and watch, for dear life; and it seemed to last for months, for years, for all eternity, as though we had been dead and gone to a hell for sailors. We forgot the day of the week, the name of the month, what year it was, and whether we had ever been ashore. The sails blew away, she lay broadside on under a weather-cloth, the ocean poured over her, and we did not care. We turned those handles, and had the eyes of idiots. As soon as we had crawled on deck I used to take a round turn with a rope about the men, the pumps, the mainmast, and we turned, we turned incessantly, with the water to our waists, to our necks, over our heads. It was all one. We had forgotten how it felt to be dry.

—Joseph Conrad, from Youth

There’s no telling what the night will bring

but the moon. That’s a no-brainer.

A no-brainer moon sitting there at its desk,

wishing it was outside

on the playground with little Rebecca Steinberg,

her hair around her shoulders

like streamers on New Year’s Eve.

The night is going to be a very long night

and I am walking into it

with my sleeves rolled up,

my cap on tight,

all my worthwhileness stuffed into my back pocket

like a wallet full of transcendental credit.

—Matthew Dickman, from Gas Station (Mayakovsky’s Revolver)

[…]the sacred becomes, after many years, secular

and then turns back around as if it has forgotten its keys,

becoming sacred all over again.

—Matthew Dickman, from We Are Not Temples (All-American Poem)

Angels are of two sorts; best not to provoke either.

—Scott Cairns, from Disciplinary Treatises, #5 Angels (Figures for the Ghost)

We carry our fathers with us

until we reach the other side

of our lives.

There we let them slump

to the ground

and walk away.

—Michael Delp, from Poem for my Father, (Over the Graves of Horses)

DEAFNESS IS A CONTAGIOUS DISEASE. FOR YOUR OWN PROTECTION ALL SUBJECTS IN CONTAMINATED AREAS MUST SURRENDER TO BE QUARANTINED WITHIN 24 HOURS!

—Ilya Kamninsky, from Checkpoints, (Deaf Republic)

I walked in my barbershop of thoughts.

—Ilya Kaminsky, from Before the War, We Made a Child (Deaf Republic)

Wind sweeps bread from market stalls, shopkeepers spill insults

and the wind already has a bike between its legs—

but when, with a laundry basket out in the streets, I walk,

the wind is helpless

with desire to touch these tiny bonnets and socks.

—Ilya Kaminsky, from Galya Whispers, as Anushka Nuzzles (Deaf Republic)

you cannot think a poem,” he says,

“watch the light hardening into words.”

—Ilya Kaminsky, from Praise, (Dancing in Odessa)

She was stretched on her back beneath the pear tree soaking in the alto chant of the visiting bees, the gold of the sun and the panting breath of the breeze when the inaudible voice of it all came to her. She saw a dust-bearing bee sink into the sanctum of a bloom; the thousand sister-calyxes arch to meet the love embrace and the ecstatic shiver of the tree from root to tiniest branch creaming in every blossom and frothing with delight. So this was marriage! She had been summoned to behold a revelation. Then Janie felt a pain remorseless sweet that left her limp and languid.

After a while she got up from where she was and went over the little garden field entire. She was seeking confirmation of the voice and vision, and everywhere she found and acknowledged answers. A personal answer for all other creations except herself. She felt an answer seeking her, but where? When? How? She found herself at the kitchen door and stumbled inside. In the air of the room were flying tumbling and singing, marrying and giving in marriage. When she reached the narrow hallway she was reminded that her grandmother was home with a sick headache. She was lying across the bed asleep so Janie tipped on out the front door. Oh to be a pear tree—any tree in bloom! With kissing bees singing of the beginning of the world! She was sixteen. She had glossy leaves and bursting buds and she wanted to struggle with life but it seemed to elude her. Where were the singing bees for her? Nothing on the place nor in her grandma’s house answered her. She searched as much of the world as she could from the front steps and then went on down to the front gate and leaned over to gaze up and down the road. Looking, waiting, breathing short with impatience. Waiting for the world to be made. [pg 11]….

….”Janie, where’s dat last bill uh ladin’?”

“It’s right dere on de nail, ain’t it?”

“Naw it ain’t neither. You ain’t put it where Ah told yuh tuh. If you’d git yo’ mind out de streets and keep it on yo’ business maybe you could git somethin’ straight sometimes.”

“Aw, look around dere, Jody. Dat bill ain’t apt tuh be gone off nowheres. If it ain’t hangin’ on de nail, it’s on yo’ desk. You bound tuh find it if you look.”

“Wid you heah, Ah oughtn’t tuh hafta do all dat lookin’ and searchin’. Ah done told you time agin tuh stick all dem papers on dat nail! All you got tuh do is mind me. How come you can’t do lak Ah tell yuh?”

“You sho loves to tell me whut to do, but Ah can’t tell you nothin’ Ah see!”

“Dat’s ’cause you need tellin’,” he rejoined hotly. “It would be pitiful if Ah didn’t. Somebody got to think for women and chillun and chickens and cows. I god, they sho don’t think none theirselves.”

“Ah knows uh few things, and womenfolks thinks sometimes too!”

“Aw naw they don’t. They just think they’s thinkin’. When Ah see one thing Ah understands ten. You see ten things and don’t understand one.”

Times and scenes like that put Janie to thinking about the inside state of her marriage. Time came when she fought back with her tongue as best she could, but it didn’t do her any good. It just made Joe do more. He wanted her submission and he’d keep on fighting until he felt he had it.

So gradually, she pressed her teeth together and learned to hush. The spirit of the marriage left the bedroom and took to living in the parlor. It was there to shake hands whenever company came to visit, but it never went back inside the bedroom again. So she put something in there to represent the spirit like a Virgin Mary image in a church. The bed was no longer a daisy-field for her and Joe to play in. It was a place where she went and laid down when she was sleepy and tired.

She wasn’t petal-open anymore with him. She was twenty-four and seven years married when she knew. She found that out one day when he slapped her face in the kitchen. It happened over one of those dinners that chasten all women sometimes. They plan and they fix and they do, and then some kitchen-dwelling fiend slips a scorchy, soggy, tasteless mess into their pots and pans. Janie was a good cook, and Joe had looked foward to his dinner as a refuge from other things. So when the bread didn’t rise, and the fish wasn’t quite done at the bone, and the rice was scorched, he slapped Janie until she had a ringing sound in her ears and told her about her brains before he stalked on back to the store.

Janie stood where he left her for unmeasured time and thought. She stood there until something fell off the shelf inside her. Then she went inside there to see what it was. It was her image of Jody tumbled down and shattered But looking at it she saw that it never was the flesh and blood figure of her dreams. Just something she had grabbed up to drape her dreams over. In a way she turned her back upon the image where it lay and looked further. She had no more blossomy openings dusting pollen over her man, neither any glistening young fruit where the petals used to be. She found that she had a host of thoughts she had never expressed to him, and numerous emotions she had never let Jody know about. Things packed up and put away in parts of her heart where he could never find them. She was saving up feelings for some man she had never seen. She had an inside and an outside now and suddenly she knew how not to mix them. [pg 70-72]

—Zora Neale Hurston, from Their Eyes Were Watching God

Remember:

when Emily Dickinson said,

“I’m nobody,” she spoke for us all.

—Richard Jones, from Comment on this: in the real scheme of things, poetry is marginal. (48 Questions)

the chill from the room

as he bends like one in prayer

to lace his boots

as he leaves to become

one of many men and women

in dungarees and hardhats

moving forward, inch by inch,

with tractors and earthmovers,

working for weeks, months,

to make a new road[….]

—Richard Jones, from Lanterns, (A Perfect Time)

A man comes in but there are no chairs,

so he stands against the wall.

He looks out the window

wondering what disease

is buried in his body

like a treasure.

If life is a miracle,

then death is, too.

—Richard Jones, from The Waiting Room, (Country of Air)

There is a heartbreaking beauty

about my crummy street

tonight, at 2 o’clock

in the first snow: I stand looking out

at this window, I think

how everything seen

is something seen for the last time.

—Franz Wright, from The Disappearing, (Rorschach Test)

Because no symbol’s going to help us.

—Franz Wright, from Church of the Strangers, (Rorschach Test)

I greatly prefer the company of the nuts, though

I will side with the sane any day.

—Franz Wright, from The Lord’s Prayer, (Rorschach Test)

This is why somebody loves

the poem […] something

that’s generally held to be

an occupation solely of the dead, […]

saying back to the earth

a few words which equal

or even rival its beauty,

its loneliness,

its disappointment and wrath.

And for what? […]

I’ve done it for the sake

of maybe 10 minutes when I was fifteen:

when I—when it suddenly—but why describe it?

[…]The few newborn

leaves more light

than leaf on a branch.

They were back—or I was.

For an instant no time had elapsed:

These leaves were not new,

they were the same ones, and I was not old.[…]

—Franz Wright, from New Leaves Bursting into Green Flame, (Rorschach Test)

….People who have never starved as our war prisoners did, who have never gnawed on bats that happened to fly into the barracks, who have never had to boil the soles of old shoes, will never understand the irresistible material force exerted by any kind of appeal, any kind of argument whatever, if behind it, on the other side of the camp gates, smoke rises from a field kitchen, and if everyone who signs up is fed a bellyful of kasha right then and there—if only once! Just one more before I die! [pg. 246]

….But it was not the dirty floor, nor the murky walls, nor the odor of the latrine bucket that you loved—but those fellow prisoners with whom you about-faced at command, and that something which beat between your heart and theirs, and their sometimes astonishing words, and then, too the birth within you, on that very spot, of free-floating thoughts you had so recently been unable to leap up or rise to.

And how much it had cost you to last out until that first cell! You had been kept in a pit, or in a box, or in a cellar. No one had addressed a human word to you. No one had looked at you with a human gaze. All they did was to peck at your brain and heart with iron beaks, and when you cried out or groaned, they laughed.

For a week or a month you had been an abandoned waif, alone among enemies, and you had already said good-bye to reason and to life; and you had already tried to kill yourself by “falling” from the radiator in such a way as to smash your brains against the iron cone of the valve. Then all of a sudden you were alive again, and were brought in to your friends. And reason returned to you. [pg. 181]

….The sixteen-hour days in our cell were short on outward events, but they were so interesting that I, for example, now find a mere sixteen minutes’ wait for a trolley bus much more boring. There were no events worthy of attention, and yet by evening I would sigh because once more there had not been enough time, once more the day had flown. The events were trivial, but for the first time in my life I learned to look at them through a magnifying glass. [pg 203]

—Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago

At one time in Old Russia it was thought that a corpse could not get along without a coffin. Even the lowliest serfs, beggars and tramps were buried in coffins. Even the Sakhalin and the Akatui hard-labor prisoners were buried in coffins. But in the Archipelago this would have amounted to the unproductive expenditure of millions on labor and lumber. When at Inta after the war one honored foreman of the woodworking plant was actually buried in a coffin, the Cultural and Educational Section was instructed to make propaganda: Work well and you, too, will be buried in a wooden coffin.

The corpses were hauled away on sledges or on carts, depending on the time of year. Sometimes, for convenience, they used one box for six corpses, and if there were no boxes, then they tied the hands and legs with cord so they didn’t flop about. After this they piled them up like logs and covered them with bast matting. If there was ammonal available, a special brigade of gravediggers would dynamite pits for them. Otherwise they had to dig the graves, always common graves, in the ground: either big ones for the large number or shallow ones for four at a time. (In the springtime, a stink used to waft into the camp from the shallower graves, and they would then send last-leggers to deepen them.)

On the other hand, no one can accuse us of gas chambers. [pg 222]

—Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago

From the thirties on, everything that is called our prose is merely the foam from a lake which has vanished underground. It is foam and not prose because it detached itself from everything that was fundamental in those decades. The best of the writers suppressed the best within themselves and turned their back on truth—and only that way did they and their books survive. An those who could not renounce profundity, individuality, and directness…inevitably had to lay down their heads during those decades, most often through camp, though some lost theirs through reckless courage at the front.

That’s how our prose philosophers went beneath the ground. Our prose historians too. Our lyrical prose writers. Our prose impressionists. Our prose humorists.

And yet at the same time the Archipelago provided a unique, exceptional opportunity for our literature, and perhaps…even for world literature. This unbelievable serfdom in the full flower of the twentieth century, in this one and only and not at all redeeming sense, opened to writers a fertile though fatal path.

Millions of Russian intellectuals were thrown there—not for a joy ride: to be mutilated, to die, without any hope of return. For the first time in history, such a multitude of sophisticated, mature, and cultivated people found themselves, not in imagination and once and for all, inside the pelt of a slave, serf, logger, miner. And so for the first time in world history (on such a scale) the experience of the upper and the lower strata of society merged. That extremely important, seemingly transparent, yet previously impenetrable partition preventing the upper strata from understanding the lower—pity—now melted. Pity had moved the noble sympathizers of the past (all the enlighteners!)—and pity had also blinded them! They were tormented by pangs of conscience because they themselves did not share that evil fate, and for that reason they considered themselves obliged to shout three times as loud about injustices, at the same time missing out on any fundamental examination of the human nature of the people at the lower strata, of the upper strata, of all people.

Only from the intellectual zeks of the Archipelago did these pangs of conscience drop away once and for all, for they completely shared the evil fate of the people! Only now could an educated Russian write about an enserfed peasant from the inside—because he himself had become a serf.

But at this point he had no pencil, no paper, no time, no supple fingers. Now the jailers kept shaking out his things, and looking into the entrance and exit of his alimentary canal, and the security officers kept looking into his eyes.

The experience of the upper and lower strata had merged—but the bearers of the merged experience perished….

And thus it was that an unprecedented philosophy and literature were buried under the iron crust of the Archipelago. [pg 489-491]

—Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, from The Gulag Archipelago Two