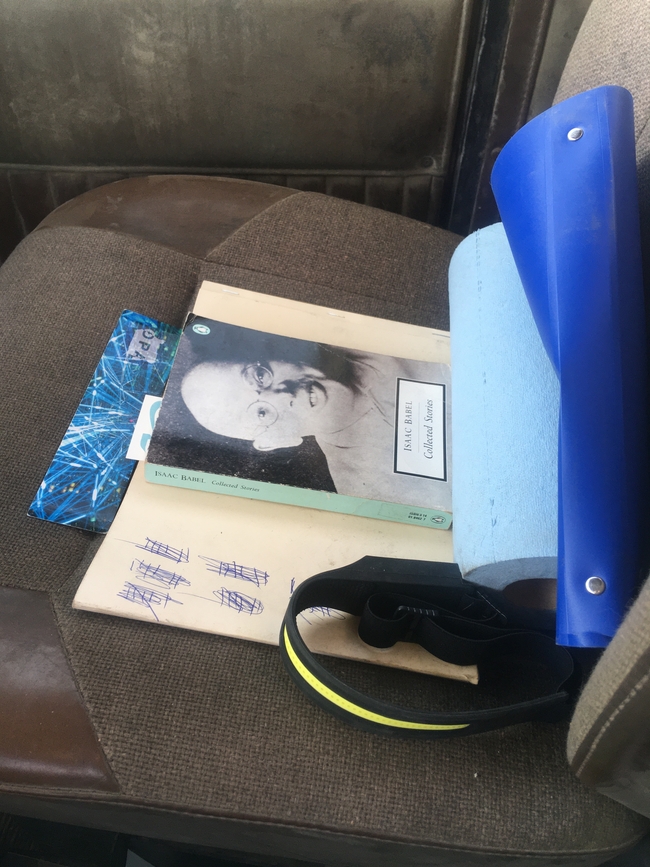

Collage

Fields of purple poppies flower around us, the noonday wind is playing in the yellowing rye, the virginal buckwheat rises on the horizon like the wall of a distant monastery. The quiet Volyn is curving. The Volyn is withdrawing from us into a pearly mist of birch groves, it is creeping away into flowery knolls and entangling itself with enfeebled arms in thickets of hops. An orange sun is rolling across the sky like a severed head, a gentle radiance glows in the ravines of the thunderclouds and the standards of the sunset float above our heads. The odour of yesterday’s blood and of slain horses drips into the evening coolness. The Zrubcz, now turned black, roars and pulls tight the foamy knots of the rapids. The bridges have been destroyed, and we ford the river on horseback. A majestic moon lies on the waves. The horses sink into the water up to their backs, the sonorous currents ooze between hundreds of horses’ legs. Someone sinks, and resonantly defames the Mother of God. The river is littered with the black rectangles of carts, it is filled with a rumbling, whistling and singing that clamour above serpents of the moon and shining chasms.

—Isaac Babel, from Crossing the Zbrucz

The woman’s soft throat swelled. She said nothing. The train was standing in the steppe. The corrugated snow gleamed with a polar brilliance. Jews were being thrown out of the carriages on to the rails. Shots rang out unevenly, like exclamations. The muzhik in the unfastened fur cap led me off behind a stack of firewood and began to search me. We were lit by a moon that kept going behind clouds. The lilac wall of forest smoked. Rigid, stubby, frozen fingers crawled over my body. The telegraphist shouted from the platform of the carriage:

‘Is he a Yid or a Russian?’

‘A Russian,’ the muzhik muttered as he rummaged about my person, ‘but he’d make a good rabbi…’

He brought his crumpled, worried face close to mine—ripped from my underpants the four gold ten-rouble pieces my mother had sewn into them for the journey, took off my boots and overcoat and then, turning his back, clapped the palm of his hand edgewise along the nape of my neck and said in Yiddish:

‘Antloyf, Khaim...’ [‘Get lost, Khaim]

I went in the snow, in my bare feet. A target was burned into my back, the centre of the target passed through my ribs. The muzhik didn’t shoot.

—Isaac Babel, from The Journey

29

Still much to read, but too late.

I turn out the light.

The leaves of the tree are green beside the street-lamp;

the wind hardly blows and the tree makes no noise.

Tomorrow up early,

the crowded street-car, the factory.

5

Her work was to count linings—

the day’s seconds in dozens.

—Charles Reznikoff, from Poems, (1920)

2

Scared dogs looking backwards with patient eyes;

at windows stooping old women, wrapped in shawls;

old men, wrinkled as knuckles, on the stoops.

A bitch, backbone and ribs showing in the sinuous back,

sniffed for food, her swollen udder nearly rubbing along the pavement.

Once a toothless woman opened her door,

chewing a slice of bacon that hung from her mouth like a tongue.

This is where I walked night after night;

this is where I walked away many years.

5

Drizzle

Between factories the grease coils along the river.

Tugs drag their guts of smoke, like beetles stepped on.

13

Sparrows scream at the dawn one note:

How should they learn melody

in the street’s noises?

18

Swiftly the dawn became day. I went into the street.

Loudly and cheerfully the sparrows chirped.

The street-lamps were still lit, the sky pale and brightening.

Hidden in the trees and on the roofs,

loudly and cheerfully the sparrows chirped.

20

It had long been dark, though still an hour before supper-time.

The boy stood at the window behind the curtain.

The street under the black sky was bluish white with snow.

Across the street, where the lot sloped to the pavement,

boys and girls were going down on sleds.

The boys were after him because he was a Jew.

At last his father and mother slept. He got up and dressed.

In the hall he took his sled and went out on tiptoe.

No one was in the street. The slide was worn smooth and slippery—just right.

He laid himself on the sled and shot away. he went down only twice.

He stood knee-deep in snow:

no one was in the street, the windows were darkened;

those near the street-lamps were ashine, but the rooms inside were dark;

on the street were long shadows of clods of snow.

He took his sled and went back into the house.

—Charles Reznikoff from Uriel Accosta: A Play and A Fourth Group of Verse (1921)

Everything is given to us by the Party and the Government; we are deprived of only one right, the right to write badly. Comrades, let us not fool ourselves: this is a very important right, and to take it away from us is no small thing. Let us give up this right, and may God help us. And if there is no God, let us help ourselves…

I am practicing a new literary genre…I am the master of the genre of silence…

I have so much respect for the reader that I am dumb.

—Isaac Babel, from a speech delivered at the first Writer’s Congress (USSR), 1934