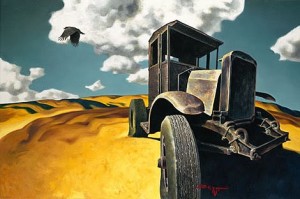

Crow’s Eye View Series, Z.Z. Wei

Crow’s Eye View Series, Z.Z. Wei

Overtime

Someone up the chain decided we should begin mining our site, the theory being that it would be cost effective to simultaneously reduce fill volume and reclaim nonferrous metals like accidentally discarded gold and even aluminum. Aluminum is far easier to find and mine from landfills brimming with tossed pop cans than it is to remove the ore from bauxite. Not to mention the effluvia of iron and steel. Whole machines from demolished factory floors and pieces of used up heavy equipment lay scattered and buried throughout the site like fossilized metal mammoths. The thinking was that since we received trash during the day, we could be open for mining after hours at night. More for less of course. The thinking was that we could work overtime and double shifts or split shifts alternating our weeks with day and night hours to accomplish this new policy and the gaping holes dug and mined by night could be filled in by day. It was a beautiful plan and the logic was unusually sound—more so than the usual bureaucratic bluster and inefficiency from above (well really below because our orders came from Houston). Since our site was in the Northwest and we received only construction and demolition waste we were prime candidates for innovative new policies, and because of EPA regulations the management of waste became big business. For these and other reasons our site repeatedly turned out to be the guinea pig of forward thinking execs.

Once the operations began, however, things started to quickly unravel—crews became confused by the blurring of day into night and night into day, heightened by the job’s already tedious expectations. The heavy weight of this took a toll that not even huge doses of coffee, energy drinks and cigarettes or chew could maintain or overcome. Some of the crew began putting back recyclables instead of pulling them out, whether out of spite or recklessness couldn’t be determined. The hostility between landfill and MRF crews worsened, and when we thought morale couldn’t suffer any more—it did. The holes that were excavated began to expose huge oceans of methane, far more than we could ever be expected to fill in the next day, and purple waves of it began tumultuously to rise and slosh. The sulfuric acid and dioxides from rainwet gypsum and waste drywall melted the soles of our boots and burned holes through our protective gear, and ruined our eyesight. The crews working at night had less supervision and therefore no accountability, because no one but peons were willing to work nights, and those peons who refused were badgered into quitting or fired. Those who remained began to drink while on duty and learned to sing shanties while they worked. The answer to the question of what you do with a drunken sailor, if raised at all, seemed obvious—give him more Bacardi. The pits dug and material being conveyored out and fed into the trommel was astounding—entire cities rested in layers below the ground, sewer systems, vaulted catacombs and crypts. Accordingly, vast numbers of corpses surfaced, floating, and even a ferris wheel and wings from a jumbo jet. The treasure recovered boggled the mind and I began to question if we had dug too far. We wore gas monitors whose screeching alarms never ceased, but our breathing and health seemed not to be permanently affected. We all knew we had inhaled lungfuls of asbestos and those who smoked on the job called the rest of us greenhorns if any brought the question of health or safety up. No one who had second thoughts ever spoke up because we realized no one was listening. Besides, the haul of booty was incredible and the crew pocketed anything they liked, so long as it was small enough to carry and stash into one’s vehicle. There were ancient artifacts, whole coin collections, jewels, electronics, and libraries full of books extant from before the fire at Alexandria, and relics of religious and great historical significance. Masterpieces previously unknown or long forgotten were unearthed beyond our wildest imaginings. We knew by what we were finding we were not asleep on our feet. We just kept on excavating, going deeper and deeper, and some built great sailing ships out of bridge timbers, using dumped phone poles for masts and fashioning black tarps used for cover as sails. After the hole reached a point where we could no longer see across to the other side and daylight failed to come they launched out over the sea with grappling cranes and implements of navigation and discovery ashipboard. They threw out sounding lines that never touched bottom. It must be like sailing a great storm like the eye of Jupiter or some other gas giant where winds were terrific. Sometimes in moments of disorientation or hallucination brought on by fatigue, we confused the ground with the night sky and sky with ground and we felt as if we floated. It seemed as if we were traveling back in time, because the glinting stars and constellations gradually warped and shifted shape, and the creatures swarming around us, swimming the waters of gas were larger and more primitive than the rats and skunks and gulls we commonly saw lurking on the edges of night, or even during the day—these nocturnal creatures glimpsed in the purple and indigo fog had great jaws and teeth and I could make out tentacled and segmented crustaceans that skittered quick like cockroaches just past the reach of lanternlight, but they had an appearance like monstrous sowbugs—or like massive trilobites or multilegged, clawed and bony-armored fish. I wanted to capture them, and like Linnaeus, catalog and name the new species, but I was never sure if they were poisonous and didn’t trust my hexarmor gloves. Secretly I was glad they feared the light, drawn but shying away.

Then one night a shout arose, “Burgess shale, boys! By God, we’ve struck Burgess shale!”

___________

Dave Mehler

Review by Pamela O’Shaughnessy

Time must seem more mysterious than ever when one works at a landfill, sorting objects which have already fallen into the past of customers, recycling some back into the present, but mainly adding to a vast pile of artefacts accreting into the past the moment they are buried and leave the ken of humans. The landfill continually moves from present discards to older and older discards, and there is no future in it. This is the opposite movement from the Arrow of Time, which moves only toward the future. A meditation on this temporal reversal seems to me to be a subject of Dave’s two poems, “Deinonychus” and “Overtime”.

I’ve learned from reading Dave’s work for a long time that the primary thing is the content, the substance of the poem. This is where the magic lies, at least in those poems where the tone is scientific, observant and detached, supporting the flight of imagination (I have also read poems of rapturous lyricism, but this “scientific” style is my favorite). This observer works at the landfill, cooperates with his co-workers, does his job well, but sees more in the work than they do, visualizing another conceptual world that strips the landfill of its seeming banality.

There’s always been tension in poetry regarding how fair it is to the reader to use unfamiliar words. Should the poem have to be understandable on its own, without resort to other informational sources? I think that question is now resolved for good, especially for e-journals: not only does the poem never need to stand on its own any more, with the whole Net behind it, but also, the instant ability to supplement a poem with obscure and specialist knowledge means poetry itself is vastly expanded as an art form. In “Deinonychus”, we google the unfamiliar title and learn it is a small feathered dinosaur that lived more than a hundred million years ago (there is much more of interest to learn about this agile little dinosaur).

So we read the poem having already learned about a small feathered dinosaur, and find that the poem is a vignette about the gulls at the landfill, dependent creatures in tune with its reversed Arrow of Time, who suddenly begin to devolve into the dinosaurs they once were, finally losing the ability to fly and reverting forever to the ground they left so anciently:

Still, unable to leave any longer, the mud found a way of reaching up to embrace them as long lost friends, or as if they always were of earth, dust, grounded, ground.

The poem carefully details this extraordinary change in the birds, but the observer takes it all in stride, because, perhaps, he too has been affected by the time-reversal of the place. It’s no big trick, he quotes some googleable authority as saying regarding the change from “scales to filaments” – and it’s no big trick, the observer also seems to say regarding this place always processing backwards, to finally join in.

“Overtime” expands this theme of Time running backward into an absorbing, headlong narrative in which the Landfill itself is the central metaphor. The workers decide to make extra money by “mining” it at night, covering up the holes they make during the day shift. The idea is that valuables are buried there, like aluminum, that might be recovered and sold. But the workers forget about their original object as they dig deeper and deeper, lost in the reversal process, exhausting themselves, caught up in the project. They dig though the centuries, the millennia, adventuring through human history and then the earth’s history, until at last they triumph, and one of them calls out in the rather thrilling ending, “Burgess Shale, Boys! We’ve struck Burgess Shale!”

Along the way are the vivid details we come to expect in Dave’s work, and we are carried along with the workers as breathlessly. They and we are called by history and find in it riches and a vindication at last. Now we google “Burgess Shale” to confirm our intuition that we have reached bedrock, and – but I will leave you that pleasure. We leave the poem wondering: who really are these workers, who have managed such a triumph by, you might say, finding the value in the forgotten “trash” of the past? And can it be that if such riches may be found in a landfill, they may be found even more in our daily lives, in the larger richness of the potential represented by our possession of a future?