Ikons

Ikons. Pure. Nechaev. Einstein’s photo. Man on the Moon. John and Yoko in bed—

to be kissing us. He is life itself, all human possibility—posted on peeling walls

in Sadr City, Kandahar, Jericho. She seems more powerful than the kills.

A photo for the ages, forever, subsides as new catastrophes flood

through. But this: joined him in the afterlife. The uproar usually

recently, the Russians shot him. So she became a bomb—

Makarov. Malign photo: guns, her lips, his shirt;

unbearably beautiful and her small finger

on the trigger of the snub-nosed

proudly in the embrace. Then

we see her black-clad wrist

clutching a long-barreled

Stekhin. She, enveloped

in love. His arm tight

around her black

robe, his hand

what we see:

a foreign

couple,

heads

tog

eth

er,

http://www.robertamsterdam.com/newser040210.jpg

in lo

ve, h

is ar

m ti

ght ar

ound her

black robe,

his hand clutch

ing a long-barrel

ed Stekhin. She, en

veloped proudly in the

embrace. Then we see her

black-clad wrist beautiful and

her small finger on the trigger of the

snub-nosed Makarov. Malign photo: guns, her

lips, his shirt: unbearably recently, the Russians

shot him. So she became a bomb—joined him in the

afterlife. The uproar usually subsides as new catastrophes

flood through. But this: more powerful than the kills. A photo for

the ages, forever posted on peeling walls in Sadr City, Kandahar, Je

richo. She seems to be kissing us. He is life itself, all human possibility—

Nechaev. Einstein’s photo. Man on the Moon. John and Yoko in bed. Pure. Ikons.

______________________

Pamela O’Shaughnessy

Review by Greg Grummer

Pam’s Ikon is wonderful in many respects. For one thing, it bristles with intelligence, right off the bat, with the list of of ikons that begins the poem. Nechaev, the nihilist. Einstein. The man, not in the moon, but on it, and all it took to get him there. John and Yoko, nihilist revolutionaries in their own right, and, along with Bonnie and Clyde and other famous couples who lived at the outskirts of or beyond the borders of convention, a palimpsest on which to begin to draw the couple featured in the poem.

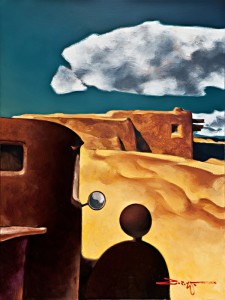

Additionally, the poem Pam gives us delightfully matches form with function. To look at the poem, even before reading it, is to experience the effect of the poem. You can see, quickly, that you will be entering a whirlpool or vortex, that you will be drawn down, swirling around yourself, that you will go through the event horizon, and emerge on the other side, yourself but different. Or, if you prefer, that you will be entering a champagne glass, set on a table, and that, if you look down, you will be able to see yourself, differently, through the table, which must be glass to allow this to happen. That the poem actually follows through on the promise of its form is truly wonderful!

Further, the poem is a delight in that it marries recent technology, bringing itself further into existence than would have been possible without that technology. So much of our poetry ignores recent advances in communication. It’s a delight to see a poet take fuller advantage of all she is offered in that regard. Yes, poetry on the internet is different from poetry on the printed page. Pam embraces those differences and uses them to her advantage and ours.

But all these things aside, what I most enjoy about Pam’s poem is what happens to me when I’m inside it. The rest of the images in the opening few lines I’m familiar with: Einstein, John and Yoko, the man on the moon. But the first one, Nechaev, I’m not. So, I google him. This establishes my use of the computer in enjoying the poem, a first hint of what’s to come. So, Necheav was a revolutionary. So, the list contains ikons of revolutionaries…the political, the scientific, (the man on the moon…hmmm, how to characterize the revolutionary nature of that?), and a couple of cultural revolutionaries. Suddenly, after their abrupt introduction, the popular, cultural references drop away, and we are confronted with, what?

Well, everyone likes a good mystery, and much of the rest of the first half of the poem is involved in the reader piecing together what Pam is on about. Apparently a picture of a man, perhaps to be found on walls of buildings–that kind of iconography. But there’s also this “she”. More powerful than kills? More on that later, perhaps? Ah, we’re dealing with a photograph. What world do these two folks and this photograph belong to? Middle eastern, Russian? And then the focus of the poem tightens to a deep consideration of the couple themselves: their bodies, their clothes. I’m not certain where I am. I’m very curious. And I’m funneling down to the resolution of the mystery. As the typography of the poem tightens, the focus of the poem tightens, until the couple themselves are squeezed out, leaving nothing but their love, and a web address.

I click on the web address, and suddenly the elephant I’d been putting together in my head is there whole, in front of me, quickly enough to resonate off of the head picture I’d been constructing. And in this immediate resolution several things come alive. The first thing is the picture itself, and its relationship to the poem I’d been creating. The second thing, and this is the most interesting thing about the poem for me, is that Pam herself comes alive– how Pam’s having imbedded the actual object of her ekphrastic observations in the poem allows the considerations of the poem to expand and include her.

In the first half of the poem, I had to take Pam’s word for how this couple is to be viewed. After journeying through the event horizon and seeing the picture for myself, I am now, as I reread the poem backwards, venturing over the same ground I had just traveled, not taking her word for anything, but rather I’m comparing her observations with mine, the things she found significant versus what I find significant, how she would characterize this couple versus how I would. The effect is, again, wonderful, organic, ineffable.

But not only has Pam changed my relationship with her, she has changed my relationship with myself. By offering me the link to the photograph the poem is based on, Pam changes who I am mid-poem. As this new person, I now encounter the poem backwards, going from love, through this couple, and back out into the larger world. All the while this is happening, this journey back out into the larger world, I’m contemplating not only the couple in a different light, but Pam and myself as well. This effect could only be accomplished this quickly by reading the poem on-line, a separate google window already open since I first googled Nechaev.

So, on top of the intelligence of the poem, its immersion in our culture, its marriage of form and function, there’s the additional delight of its modern-ness, and the feeling I get of having been changed by the poem, of how it has involved me in an organic process. I not only get to contemplate the poem, but what the poem might mean for the future of poetry, one of the many directions poetry could be headed after passing through the event horizon of modern technology.

Although I have read a lot of poetry, I have never had this happen before. And that’s what happens to me all the time when I’m confronted with poetry. A new experience, a new world, a new me.