Pages from A Field Guide to the Birds of Mars:

an Interview with Charles Hood, conducted by Dave Mehler for TCR

TCR: Your most recent book, A Salad Only the Devil Would Eat, is a collection of essays put out by Heyday Books, about the uglier, more austere and ignored parts of the natural world. This book is not Barry Lopez or even John McPhee—yet not unrelated: maybe more quirky and funny, and uniquely reverent? Full of your personality and outlook on things. Would you plug your book and tell us a little bit about how it came about and why?

CH: Heyday let me have fun with this one: fourteen photos, fourteen essays, and all the sarcasm, trivia, and Melvillian cetology fit to print. It started as one thing, ended as another, and in between it covers feral monkeys, mutt dogs, smudgy journals, brutal divorces, the red dye that made Spain rich, and the obsessive insanity that is competitive bird listing. Jonathan Franzen likes this book anyway, if that counts for much, as does the Los Angeles Times and pretty much all the other reviews I have seen so far. Here is the backstory. There’s a journal out of Santa Cruz, Catamaran, that is art, poetry, essays, fiction. I was in the second issue—somebody told me oh, why not submit, and I did, and one thing led to another, and I submitted other pieces too. I probably have been in their journal more times than anybody else? Those essays became the core idea of this collection.

Heyday as a press happened for me because they were planning to do an anthology about Los Angeles, and a different friend said why not give them a pitch? So I wrote up a proposal to do urban trees. Now at the time I didn’t know fuck all about trees, but I very much wanted to learn. Out of 180 proposals, they accepted twenty, and mine was one of them. So I learned about trees and the book got good reviews. I then pitched an architecture book, but that didn’t go through. As a consolation prize I ended up doing a bird book and a mammal book with Heyday and I have three other books I will do with them over the coming years.

One quibbling correction is that Devil Salad is not my most recent book… that would be a field guide to herps called Sea Turtles to Sidewinders: A Guide to the Most Fascinating Reptiles and Amphibians of the West. It came out two months after the essay book. Prose is not all that jazzy in that one but it has some seriously great photos. After those two, I am still under contract to do another four projects—one with Timber Press and three with Heyday—all of them in various stages of abandonment and disarray. I need to get going. Idle hands are the devil’s workshop.

TCR: What’s your opinion on handouts/awards/grants and residencies to artists and poets? Should one pursue them or take them? If so what’s the secret to getting them if you’re a nobody poet at a landfill driving a truck in circles?

CH: Art grants have their own culture, and there are three things to remember about them. (1) The awarding bodies are often arbitrary and capricious. I have many examples of being the brightest flower in the room only to have the award go to some drab weed who not only had not earned it, but who, in the end, made nothing of the opportunity. What can I say? Life is not fair. (2) The application is not about you, but about them: what do they get by sponsoring you? (3) Active verbs and a compelling narrative—tell a story that is better than everybody else’s story. And I guess the fourth note is that winning a poetry grant does not mean you are a poet (it just means you fill out forms well); conversely, not winning one does not mean you are not a poet. Want to write? Go write. Don’t worry about awards and who got what. Getting published in Triggerfish, that is the best revenge.

TCR: Some friends of mine and I are in love with Charles Wright’s recent book of poems, Caribou. I see that he was a teacher for you getting your MFA. Can you tell us some stories on him?

CH: Charles Wright helped me decide to go to graduate school, but not in the way one might guess. As an undergraduate I usually worked as a school aide in the morning, took afternoon classes, and then worked in a mountaineering shop at nights and weekends. I also did yard work, I worked in a factory for a while, I did freelance editing. Anything, really, just to get by. One day I got sent to Orange County to make a delivery. Why I was not in class myself, I can’t remember, but on a whim, since I was already in the area, I decided to visit UC Irvine before going back to L.A. This was pre-GPS, so I dead-reckoned my way to campus, found an illegal place to park, and wandered around like a rube in Bergdorf’s until I ended up in the English Department. Right then somebody walked by with a copy of The Cantos under her arm. It was as if it had been scripted. She was on her way to an Ezra Pound seminar with Charles Wright. Since I was (and am) largely self-taught, this seemed to me some vision of Paradise and the Seventy-Six Virgins—what, somebody could guide you through The Cantos, maybe even help it make sense? Sign me up! Of course once I got into graduate school there, Charles Wright never offered that class again, and then he left to go to University of Virginia. So I still remain on my own with Uncle Ez. I did though get to do Gertrude Stein with Marjorie Perloff, who later became president of the MLA, and I also attended lectures by Jacques Derrida himself. Didn’t understand them, but I was there. His secretary once tried to steal my adjunct office desk.

Here is one Charles Wright quote I still use: “Coyotes, cockroaches, and the sonnet will always be with us.” And there was one topic about which he and I fought bitterly, which was the then-nascent post-mod club called “Language Poetry.” The name infuriated him, and he would say in exasperation, “But all poets are language poets.” I did take a seminar with Wright in traditional meter and form; for the final exam we had to scan Hart Crane’s “The Bridge.” I got the highest grade in the class, and so somebody please carve that in granite on my tombstone. I am not sure Mr. Wright knew what to make of me—among other things, when I started school at Irvine I had been living in my car at the Grand Canyon. Before he left I asked him for a letter of reference to put into my job placement dossier, and he did it, but he wrote it by hand. That was very passive aggressive since his handwriting is illegible. If you were one of the ten people in the world who happened to be his personal friend, you would recognize his back-slanting letters and maybe even be able to read half the sentences. For the other 10,000 job search chairs in academia, the document was utterly useless.

TCR: How has the pandemic, the political climate, and the cultural moment affected your ability to teach, travel, and get the artistic and educational work done?

CH: Sure, like many of my other friends I lost money because of cancelled gigs and forfeited travel deposits. But unlike some of my work colleagues, I loved the teach-from-home scene. My out-of-pocket costs dropped (no more driving to campus meant no petrol to purchase), and the social costs lessened as well (no more insincere and tedious socializing going to / from the copy machine). Overall, I am a fan of pandemics: we should have them every ten or fifteen years. They help thin the herd and they allow the freeways to quiet down. Fewer pumas get hit by cars during pandemics. And, yes, mandates or no, I still wear my mask to the store. Why? To quote a page from my covid notebook, “people are poison.”

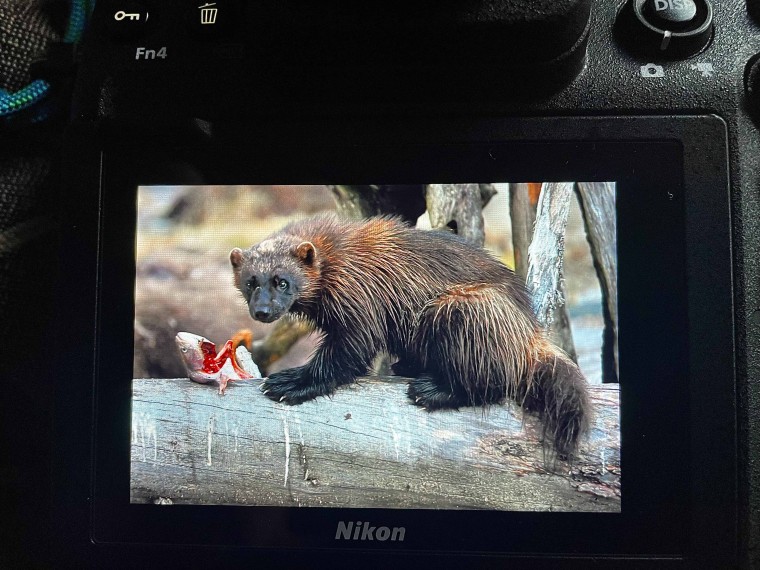

TCR: So, in a few short weeks you’re retiring after 32 years as an English prof at Antelope Valley Community College, and you’re purported to be heading to the Finnish border to go take a close look at wolverines. What else do you hope for and expect to accomplish now that you’re unshackled and free to use your time as your own? What will ‘retirement’ hold and what does it look like to you (I’m imagining more activity and movement and work than ever for you? Just differently directed?)?

The way my pension is set up, once I quit teaching then I get a one-time payoff, money I have earned but could not access. That means I will be able to join the landed gentry for about twelve or fourteen months, or at least until the money runs out. That means that long-deferred dreams like Borneo and Madagascar can happen, along with briefer pivots such as Paris and Helsinki. That magical state of being is not here yet; for now, I am still in harness. What the future will be like is hard for me to imagine—I just am focused on serving out my current sentence and hoping that all goes well at my next parole hearing. Freedom? I have heard it talked about. Who knows, like the Yeti, it may actually exist.

TCR: What’s the secret to getting good shots as a wildlife photographer. Is it a little bit like hunting with a rifle or bow?

CH: Really good wildlife photography is easier if one has fancy lenses and good editing skills, but it starts with basic fieldcraft. If I could give one piece of advice to anybody who wants to see more birds or more snakes or even hope to encounter the mega-thrill things like puma and wolf, it would be, Hey idiot, shut the fuck up. So many people blunder down the trail barking nonstop like Chihuahuas lashed to megaphones that it’s a wonder the other hikers don’t just smash their heads in with rocks. Honest to gosh, I have heard people coming from over a quarter mile away, and trust me, I have bad hearing, thanks in part to being hit in the head a lot as a child. (To quote one of my own poems, back then we didn’t call it child abuse, we just called it growing up.) If I can hear you coming, that means so can every animal across the next three meadows. You don’t just ruin it for yourself: you scare off everything for the rest of us. And it has to be a complete package. I see people who have bought after-market camo wrap to disguise their white Canon lenses, and yet they themselves are wearing red sneakers and a white ballcap. White is usually a warning flag: when a deer turns and runs, it flashes its white tail. Rule number one: don’t wear white in the woods. And final thing, most people start too late. If it is spring or summer and you’re just getting to the parking lot at 9 a.m., you have already missed the four most important hours of the day.

TCR: What was home life like growing up for you, and how did you find your way toward writing, poetry, photography and the academic life?

CH: Poor people of the world unite! I had whatever normal was back in the day: mom, dad, brother, bikes in dirt lots, red meat and Hi-C, sugar cereal for breakfast, church every Sunday, and lots of drama and trauma in the neighborhood—gangs, alcoholism, poverty, spousal abuse. Later I went to a white suburban high school but didn’t fit in there, sort of “too little too late” maybe. Had any of the other kids in high school had their face held down in the cereal bowl until they drank up every drop of milk? I don’t think so. Though I will say this about my father. I may have my grievances—I was sexually molested, and my parents blamed me for it—but I will say that my Depression-era, World War II-serving father knew how to work and how to work hard. He was a cowhand who became a delivery truck driver, and never complained, never took a day off, never asked to eat first or have the best of anything. He passed that on to me, and God bless him for it. Otherwise there was a lot we never talked about as a family, from my grandmother’s alcoholism to my mother’s need to be verbally cruel. It did not set me up for success; I don’t just mean that there was no college fund, but I mean even basic things, like I have spent too much of my life in bad relationships, assuming that tension and misery were normal. Note to self: not true, not true. One can be (and one deserves to be) happy.

I went to college using the backdoor of a community college, and from there a Cal State, and from there UC Irvine. I remember my poetry teacher at CSU Northridge asking me if I wanted to go to graduate school. I said that sounds good, what’s graduate school? Later I started a PhD in American Studies but dropped that to do a Fulbright. There was some family drama going on too, so that was another issue in trying to get a degree past my MFA. It was all ad hoc and duct tape, my life back then. Yet at the same time, language would not leave me alone: anywhere I ended up, I found I was still a writer. Not a very good one, but for me, I hear, taste, dream, experience the world through language. Half of my students can’t tell the difference between “then” and “than,” visually or aurally. That just baffles me. It would be like not being able to tell a C major on a concert piano from somebody banging on a piece of tin with a ballpeen hammer. I gave away a library of over 1,000 poetry books, and as a guess, I still have 5,000 books left over. Language—wow, almost as good as sex. Whoever invented language should get free Krispy Kremes for life.

TCR: So, I hear there’s a book manuscript of poetry in the works for you (and you’ve refused to let me take a look at it, even though Triggerfish had published a few poems from it). Judging by that sample this collection may be your best one yet? Still you have said in another interview with Foreword magazine, that it’s gone through 22 versions, and it’s refusing to cohere as a book. I’m sure some of our readers may know something about this experience from their own writing? I recently heard Carolyn Forché in an interview talk about this in regards to her recent memoir What You Have Heard Is True, saying that she struggled for fifteen years or more to write it until she found a way to cast and frame the narrative, then all the pieces finally came together. Would you be willing to elaborate a bit about this struggle? Any guesses as to where the problem lies at this point? Are you just seriously ambitious and a perfectionist with unrealistic expectations, just still not done writing for it, or maybe for this book at this point in your life expecting more from it, what?

CH: I guess one problem is lack of interest—or more accurately, lack of time? Because I have such expensive obsessions in relation to a teacher’s salary, I always am grabbing extra classes to pay for the next lens, the next trip. Since cell phones have gutted the entry-level camera market, that means top-end kit has no subsidy. Nikon et alia have had to become niche manufacturers, not that different from Audi or Bentley. The main companies still make great lenses and interesting cameras, but it’s all in smaller quantities than before and priced like luxury goods. As one example, there’s a new Nikon telephoto lens everybody likes, except it’s $14,000 plus another grand in Los Angeles County for the ten percent sales tax. Even if you had that money—and I for one don’t—there’s a year’s wait to get one. But if I can boost my income a bit above baseline, then I can get not a $14,000 lens but maybe a $2,000 lens—or I can so long as I am willing to work a double or triple class load. With a schedule like that, poetry often gets pushed back on the to-do list behind the necessities of keeping up on my multiple jobs, multiple lives.

More than that, fundamentally I am at war with the poetic line: some pages very much are prose poems, and yet adjacent content seemingly still is lineated, and the manuscript keeps switching modes in a way that just does not work. I need to pick a central pattern or cadence and stick with it, and that has not happened. Who am I on the page? I wish I knew.

TCR: Any advice to younger writers or aspiring poets? Photographers?

CH: Trust your voice, read everything, submit everywhere, trust your voice, master your craft, go places, do things, trust your voice, and if you haven’t yet read everything, time to get started. Yes, eventually you will be published. Good work always finds a venue. Until then, master your craft. Did I say that? Oh yes, and read everything. I have students who know that Colossus is a roller coaster at Six Flags Magic Mountain but not that it was Sylvia Plath’s first book and it also was a tall statue on the island of Rhodes. To be a good, interesting poet you need to know all three types of Colossalism, and maybe a few more besides. Go to readings. Go to the ballet. Go watch the trucks drive in circles around the dump. Take the cheapest flight you can find this weekend that goes to the strangest, furthest-away place. Read EVERYTHING. You can play video games later. You can sleep when you are dead. Stop complaining and go DO something.

TCR: Many concerned writers (poets, novelists, and eco writers) in panic mode are suggesting we are in the midst of climate-collapse and the apocalypse is now. Climate change and mass species extinctions, the oceans are dying, epic year-round wildfires, and the end of the world is eminent even if we don’t know it yet. What are your thoughts about this? What are the realities from your experiences and travels on the ground? Are there any positive signs or reasons to hold out hope or is it all doom and gloom? Also I suppose what’s in our power to do about some of these things besides write about how the world and the future of the planet is coming to an end?

CH: The world will survive us. Now will we survive us? I give it fifty-fifty. Until then, lead a good life, write good poetry, and remember that the world never has NOT been in crisis. These times are no better nor worse than most other times.

TCR: You’re the featured artist for this issue, and originally I was soliciting aerial photos from you, but those turned out to be under copyright—so we went with a lot of other photography from your vast store of various portfolios. All I’ve done so far is ask you about poetry and writing. What’s more important for a photographer: their vision or their competency and craft with their camera—or luck? How does one’s personality enter into it as a nature photographer? Does it?

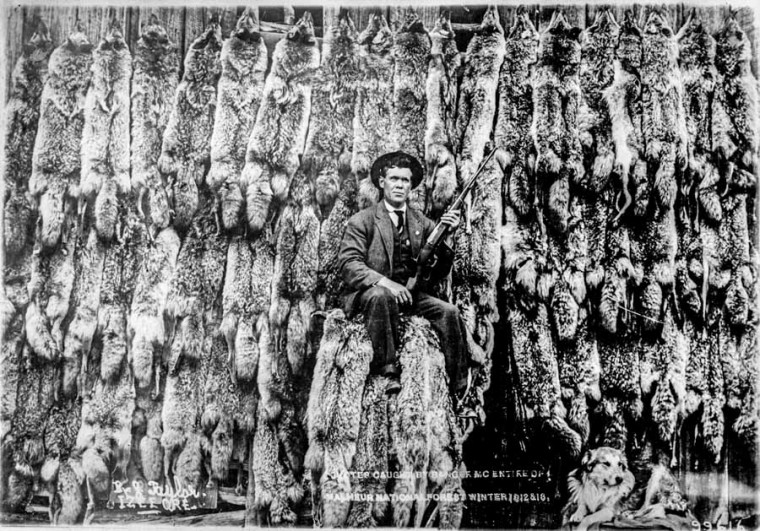

CH: I call the photo series in this issue “human/nature,” and collectively it expresses my sense of how strange and yet marvelous the world is, from the shot of the birdwatcher and the dead alligator to the found poetry of road signs. This is my private work; most of what I get paid to shoot is more conventional: pretty birds, pretty scenery, level horizons, blooming plants. If there is a great blue heron, most of the buying public wants to see it photographed on the edge of a lake, not perched on an upside-down shopping cart in the Los Angeles River. I’ve been in editorial meetings where the expression “nature porn” comes up—as in, I need to have more of it. Even so, my quirky tastes sneak in; most books I have been involved with have at least a few historical photos, and in my mammal book, there is an F-18 flying through Star Wars Canyon in Death Valley. My bird guide ends with pictures of just dangling feet; the rest of the bird has already flown away.

TCR: What were some of the best things about being an educator in higher ed and some of the worst things? Care to share?

CH: One pleasure is how many interesting people you get to meet, mentor, watch flourish and outgrow you. My students have gone on to publish books, win awards, study abroad, finish MFAs and doctorates. I was at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco once, and somebody called my name—a former student was a curator there, and happened to see me in the galleries. I had no idea she had made it so far; she had grown up in the far corners of the desert. Other times students can be lazy and dim, and that’s a drag, and some (not all) administrators can be lazy, dim, and cause active harm, and that’s even worse. I have a colleague who teaches biology. Standardized course: there is a textbook, there are lectures, there are labs. To make it convenient for the students, he took all the strands of material and collated them into a single study packet, so they could review for exams. He didn’t alter the textbook or add extra material; he just took the existing material and made an “all in one place” packet. A student filed a complaint against him because (the complaint alleged) the study guide was too hard. Yet it was just the textbook material. I bet that the student was not reading the book either, which I often face as well. Part of my job may seem heavenly: some days I may be home before noon, grilling chicken and pouring a glass of Chardonnay, ready to eat it on the back patio while I read Milton aloud to the dog. How about some Trader Joe’s cheesecake for dessert? But the flip side of that is always being under attack from students and administration, and never being off duty: students routinely email at 10 pm on Sunday night. Some of my friends won’t respond that late, but I find it usually solves problems faster just to deal with things as they come up. When I am done for good, I won’t miss it, or so I say now. When the money runs out in a year or two and I have to take part-time work as a wedding photographer, I am sure I will look back on teaching and sigh for the good old days. How about where you work—can you get me a job with Waste Management? I have good qualifications: I have been shoveling shit all my life.

TCR: You’ve traveled widely, written a book of poems about your experience as a scientist in Antarctica, told me some stories about New Guinea and other places like Inuit burial grounds. Is there anywhere in the world you haven’t traveled to but have always wanted to? If offered the chance to go to Mars (where btw there are no birds), would you go? If so, what would most capture your attention, hypothetically?

CH: I am a landscape junky. Of the fifty pieces of art in my house, my all-time favorite is an aerial photo of the Great Basin by Michael Light. It is abstract and yet specific; it could be almost any planet, but it definitely “is” a planet: there is geology and history and the flow of water over time. That Carson Sink photo faces a four-foot by four-foot shot of the moon taken from outer space, printed from a file acquired from NASA. Because there is no atmospheric distortion, the view has stunning clarity and detail. I framed it behind the cleanest, purest, highest quality museum glass commercially available. If I had known that amateur space travel would be possible in my lifetime, I would have made making money a much higher priority. Fifty million dollars to go into space? Seems like a bargain. I will say though that there are birds on Mars, or at least in an artistic sense. I once won an award in an art contest by painting a hypothetical plate for a field guide to Martian birds. My animal was based on a bird called a stone curlew and the explanatory text was in my own made-up Martian language, which was written in a hybrid between Icelandic runes and Innuit pictographs. There even was a range map. What I got wrong was the tone of the light. We know now how murky the Martian sky usually is, like trying to paint plein air using tomato soup, not watercolor. Two great literary takes on Mars: Ray Bradbury of course, Martian Chronicles, but let us pause to tip our hats to Edgar Rice Burroughs and the John Carter of Mars series. (The 2012 movie deserves more love than it gets.) I am not obsessed, but it is true that I recently downloaded a night view of the Earth as seen from the surface of Mars. I am trying to convince my co-author that we can make room for it in a book with a working title of Nature After Dark. From the gravel plains of Mars the home planet may look no brighter than a mediocre star, but it’s our mediocre star, and I am strangely fond of it.

You can find a few of Charles Hood’s books, including field guides and A Salad Only the Devil Would Eat, from Heyday here: https://www.heydaybooks.com/authors/charles-hood/

A couple of my personal favorite books of poetry by him are South X South, and Partially Excited States. A link to a few more titles are here: https://www.thriftbooks.com/a/charles-hood/377916/