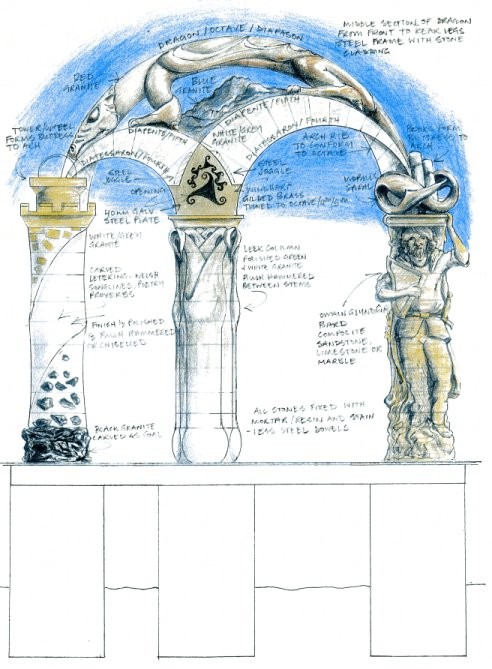

Wales Arch Drawing, Duncan Moon

Wales Arch Drawing, Duncan Moon

Jorge Luis Borges in the streets of the French Quarter, 1980

He came to hear jazz

to feel the irregular sidewalks

beneath his leather shoes

to receive an honor

for being himself. 10K as I remember.

We were gathered in a half-lit space

a large hall, starkly furnished,

a watering hole for the International

Chamber of Commerce, overlooking

the Mississippi. Perhaps 100 men.

The Borges sat alone along a wall

lined with grey metal chairs.

Suited businessmen wholly ignorant of his writing

busied themselves in distant clusters.

A wooden podium unadorned

centered at the room’s front.

No evidence of a host or ceremonial head.

And me, with twin shopping

bags of books, mine mostly, the rest

from a Quarter bookstore I managed,

lugged there to be signed.

He and I sat against the wall

where I tried to make him welcome

in a world as alien to me

as to him. I kept silent

that I had read everything

he had written, in all its transliterations.

I debated the ethics of asking a blind man

to sign a book, much less the 30 I had.

As a compromise with myself

I scaled back my hopes, opting instead

for a single book, a book of his choosing.

The fifth book I pulled was Dreamtigers.

A 1st edition hardback. His first

American published translation.

His face grew wide, his eyes smiled.

The choice was made. A book I had found

in downtown Dallas as a teenager

where I told my parents I was going to movies,

but always returned with bags of books.

This Borges took the pen I put in his hand

and quickly opened the book to its endpapers

and would have signed across Antonio Frasconi’s

woodcuts if I hadn’t taken the book back

and opened it to its title page. His hand

took over and Borges reappeared on the page.

I wanted him to know

that I had his back, even if Maria wasn’t there

I would be his eyes, but not ears

as it happened. When the whining microphone

began its twisted feedback,

a preamble to the ceremony beginning,

and the palaver overtook us

I found myself a partner,

a co-conspirator with the awardee.

As the praise continued, as the audience

adjusted, and the surreality evolved,

I saw his face grow wide with wonder,

with glee. I heard what he heard.

I saw what he imagined

and laughed when he laughed

when he was credited with an award

he deserved but was never offered.

Never even nominated during his life.

I watched him walk unaccompanied

to the podium, and accept his Balzan Prize.

Ambassador of art? Keeper of the sacred metaphor?

What was he to them? A monied mystery?

I left with my copy of Dreamtigers,

and returned to the open zoo

that was the French Quarter, never guessing

that the next morning

Borges and Maria would rise

the three worn steps into my bookstore

and he would ask about Conrad,

did I have any Conrad on my shelves.

Joseph Damn Conrad, whose books

were an invisible letter in my alphabet.

Or did he already know that 30 years later

my Dreamtigers would also go missing?

______________________

Richard Weaver

Review by Kurt Luchs

There are many things to like about this poem, starting with its subject, Borges. No moment spent in his company is ever wasted. It’s also a poem with built-in appeal for book lovers. But mostly (as Thomas Lux says in his poem “Commercial Leech Farming Today”), “I like the story because it’s true.” This anecdotal but carefully constructed piece tells of a real-life encounter between a poet and one of his idols, an idol who does not disappoint, however disappointing the context. Weaver starts by alluding discretely to the writer’s blindness in the gentle opening stanza: “He came to hear jazz / to feel the irregular sidewalks / beneath his leather shoes…” His witty reference to Borges receiving “an honor for being himself” is literally true. The Argentine genius spent much of his last decade traveling in foreign lands picking up random, if well deserved, prizes, though never the Nobel Prize. It was almost certainly the combination of his Catholic religion and moderately conservative politics that kept it from him. The rather sad little awards gathering described here is completely believable. As usual, the master of ceremonies gets everything wrong, and as Weaver notes, Borges “laughed / when he was credited with an award / he deserved but was never offered. / Never even nominated during his life.”

Weaver, a character in the poem as well as its author (how like Borges!), has his own agenda. As a fan and also as the manager of one of the finest used bookstores in the Quarter, he would like to get some books signed by the great man. However, as he says wryly, “I debated the ethics of asking a blind man / to sign a book, much less the 30 I had.” The pure admirer within him battles with the rabid ruthless fanboy and the admirer fortunately wins. He decides to ask Borges to sign only one book, a copy of Dreamtigers which, it is implied but never directly stated, was the first book by Borges that Weaver ever bought and read.

That would seem to be the climax and end of the poem, but instead there is a surprising and poignant coda. The next morning Borges and his wife make an unannounced visit to the bookstore that Weaver runs. The man who always thought of himself as more of a reader than a writer; the man whose first language was English, not Spanish; the man who admired British and American writers above those of his own country – that Borges entered Weaver’s shop and asked if he had any Joseph Conrad in stock. Which of course he did not. It’s the only time his hero will ever ask him for anything, and he doesn’t have it. Remembering it decades later, the thought of the missing “Joseph Damn Conrad” still makes him seethe. I take this as a subtle metaphor for how the writers we love most have given us more than we can ever give them. As W.S. Merwin writes in “A Debt” from The Lice – which I take to be about Sylvia Plath – “It is a true debt it can never be paid.” The loss of the precious signed copy of Dreamtigers is mentioned almost as an afterthought, and makes a suitable finish. The classic book was written and published a lifetime ago, Weaver encountered it by chance and it changed his life, perhaps being an important signpost on the road to his becoming a writer. It was there, and now, like Borges, it is gone, yet the memory remains. And what a lovely memory he has made of it.

Review by Robert Joe Stout

The ease with which Weaver tells his poetic stories slides one deftly into the New Orleans he writes about. I liked being there with the author and Borges, sharing a literary event that like several I’ve experienced—chairs against a wall, businessmen in the doorway, a surreal merging of poetic wonderland and everyday downtown bustling. The blending of caring and irony is feel-good smooth; the conclusion appropriately realistic (where is my New Orleans cookbook that Frank Gross inscribed with colored ink French Quarter curlicues?). Both the author and Borges emerge as real live personages; I felt delighted to meet them and share their experiences.

On the other hand the Oyster House poem, though well-told, seems a bit disjointed. Weaver’s mastery of detail and description seems to dissolve when the person in front of him abruptly collapses; the alert, accurate observer becomes intellectually subjective making this reader wish for elaboration of what would seem to be the catalyst for what’s happening in the poem. Nevertheless the writing has vitality and the New Orleans characterizations are very well done. I lived in the Irish Channel there for several years, though before the time that Weaver describes. Both poems prompt one to want to read more of Weaver’s work.