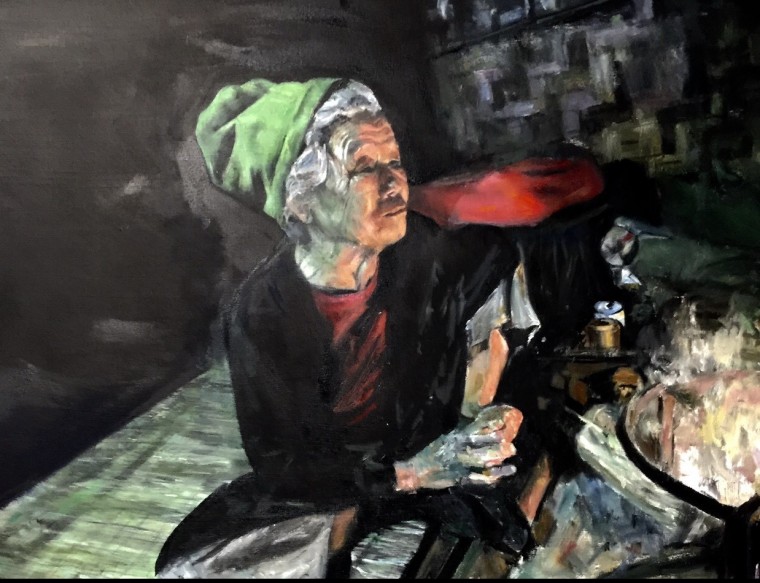

Gillian Sargeant, Old Lady, 3′ X 2,’ oil on canvas

Gillian Sargeant, Old Lady, 3′ X 2,’ oil on canvas

THE LIMITS OF COMPASSION (After Su Tung Po)

The hollyhocks have

risen above my door.

They’re amazing to behold.

The aroma of phlox

is honey to my nose.

And the irises grow

where nothing else

seems to grow.

It’s almost a miracle.

Paralyzed,

from her neck down,

the old woman

across the road

stares at those flowers

all day. I pray

it gives her pleasure

and eases her cares.

But it’s a pleasure I hope

I will never share.

_____________________

George Freek

Review by Andrea Jackson

I wish I could read the original (Chinese?) poem. I like the subtlety of recognizing that even while wishing pleasure for the old woman, the speaker appreciates his own good fortune which, if it continues, means he’ll never experience that particular pleasure.

Review by Mark J. Mitchell

Chinese poetry has been familiar to English speakers ever since Ezra Pound’s Cathay. At least, we thought it was familiar to us.

Like most people I know, I have only met these poets in translation and, to quote Frost, “Poetry is what gets lost in translation.”

In my reading I have learned that there is much that is inaccessible in the poetics of China. There is the musicality of the language to begin with. Like actual Chinese music, it comes at us with a different scale. Also, because of the agendas of early translators, most of us don’t know that all classical Chinese poetry rhymed.

Like many of my generation, I am most familiar with the great T’ang poets, Tu Fu, Li Po and Wang Wei. I know these poets in versions by Ezra Pound, Kenneth Rexroth, Gary Snyder, Burton Watson and David Hinton.

Now George Freek presents us with two poems from leading poets of the Sung Dynasty (C. 1000C.E to 1225 C.E.). I don’t know if these are translations or just imitations of the poetic voices of these poets. I could not find other versions of these poems either in my several anthologies of classical Chinese poets nor on line. Not really surprising, Su Tung Po alone has left us over 2,400 hundred poems. When I work from another language (French, Latin and Occitan) and label the poem “after” I mean that a certain poem and poet are the jumping off point but please don’t fault me as a translator, I’m an imitator in the Robert Lowell sense.

“The Limits of Compassion (After Su Tung Po)” is a lovely small poem that could take place anywhere—ancient China, a contemporary suburb in Illinois, say. The speaker is observing flowers and trees both visually and through the scents. He sees an old woman across the street. He wishes not to share the burdens of her old age. As a Chan Buddhist, he knows that he will.

“Ice on the River (After Mei Yao Chen)” is another poem that deals with aging. This time the winter weather stands in for the degeneration of the body and soul. The central pain of the speaker is the death of his wife over the last year. Mei Yao Chen seems to come from more of a Daoist point of view, where there is no choice but to let time flow.

What truly astonishes me about George Freek’s versions is their musicality. They both have an element of rhyme without ever falling to a pattern. There is an internal chiming and echoing of sounds within the lines that enhances the meaning and the imagery within the poems. These versions seem to sing in a minor key.

Thanks for these versions, George.