Experiencing Dan Flore’s Chapbook lapping water

Review by Pamela O’Shaughnessy

Dan Flore’s first book of poetry, lapping water, presents the voice of that quiet, nature-attuned man who observes without judging his own changes and the changes of those closest to him. These are unassuming and personal poems that do not partake of the ironic, subversive, rootless postmodern, but instead look to romanticism, imagism, and even further back, to the timelessness and transparency of such emotive lyrical poets as Po Chu’i and Tao Ch’ien a thousand and more years ago.

Another place to look for poetry such as this is in poetry from other countries where self-consciousness does not complicate and second-guess the emotion. When reading a chapbook from one who stands to the side of the academic poetry of the day and insists on the plain vernacular and purity of feeling, one can only evaluate it through the heart.

A third place to look for the depth of emotion and theme of loss often displayed in lapping water is in Flore’s teaching of creative writing classes and leading workshops that, as he writes, “use the writing of poetry as a recovery tool for those suffering from serious mental illness.” He feels that he has been influenced by his students: “Sometimes when they read me one of their original poems, written for the specific purpose of coping with their affliction, I am reminded just how powerful poetry can be. Anything that can move both author and audience to tears and inspire people to overcome adversity must be given the respect it deserves.” Poetry in this context takes on a dimension that isn’t often spoken of these days: it is performative language, not just a text to be experienced aesthetically. It is a process that may lead a reader and writer to experience a healing catharsis. The words present a scene that is experienced in the process of reading, and the reading become a healing act.

Flore also mentions influences from writers as broad-ranging as Kerouac, Ginsberg, Mary Oliver, Rumi, Neruda, Rimbaud, and Billy Collins. It is true, lapping water has some of the free-flowing and impromptu style of Kerouac and Ginsberg, the immediacy of the moment in Oliver’s work, the primacy of emotion through image found in Rumi, Neruda, and Rimbaud, and the vernacular style of Collins. But these influences in no way overwhelm Flore’s style or poetic concerns.

Overall, there is a unity of style and theme. There is a sense throughout of the ability of natural places like forests and streams to re-vivify the narrator and allow the calm reclamation of memories. There is loss and mourning, awareness of transience (again closer to the ancient Chinese than to the more flippant age we write in). There is a religious or at least mystical faith. There is a painful childhood, and overcoming all this. But the intent is not to uplift or inspire, as such, it seems to be to feel these emotions and allow them to dissipate. There is little preaching here, and little of the pep-talk. Healing doesn’t happen through talk, it happens through re-enactment.

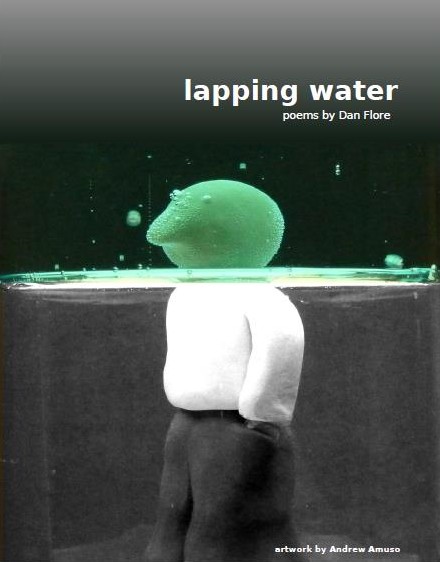

lapping water was published this year, with sensitive and whimsical black-and-white illustrations by Andrew Amuso. Flore is a regular contributor to The Critical Poet, and this reviewer has seen the development of his poetry toward increased power, structure, and confidence over a period of several years. He has written that he has been “born and bred” on poetry workshopping boards, which are becoming alternatives to academic publishers and provide a freedom to experiment and grow without pressure or any insistence on the current fashion; and Flore is an example of the kind of young writer who flourishes in such an environment. A second collection will be published soon and is likely to take the poet into deeper inner waters.

In sarah’s letter the reader is presented with mysteries: who is the speaker? Who is she writing to? The first lines identify someone who is distant from the recipient of the letter, evidently a child:

who tickles you

with nursery rhymes

Who is this writer and what is the connection with the child? From the title, “Sarah” may be a mother; but if so, why is she not with the child she thinks of?

Some of this is answered later in the poem:

it was only you and I…

So this is a biological mother, or a surrogate mother. Is she a mother whose child has been taken away, or abandoned? The child lives with another mother now. And something is wrong:

I will hear you too

The narrator-mother expects her to cry out at night. The separation causes a crying out on both sides. This is confirmed toward the end of the poem:

in some night

that pounds and whips without mercy…

Which mother does the child call out for? Is it the night that is violent and cruel, or is the narrator-mother afraid that the other mother may treat the child that way? We are left not knowing, but with a strong feeling of sadness, loss, and helpless worry, with unresolved questions written into the wind.

sarah’s letter exhibits many features in common with other poems in the collection. The language is accurate, but doesn’t call attention to itself. Punctuation is generally absent, and the line breaks remind one of Pound’s pronouncement that a line should follow the musicality of the phrase, not any notion of balance or equality of length.

The diction, though, is carefully chosen. This is not really a letter to a little girl; who would speak of a night that pounds and whips? Though most of the language is simple, toward the end, the poem unabashedly changes diction:

what majesty has been born from your imagination?

To the question, what are we reading, then, we seem to be reading Sarah’s letter — as it begins, to the little girl, but in the end, to herself.

In another poem, I run with the ghosts of deer, after the narrator experiences a car accident, there is a new feeling of vulnerability. The poem begins:

we circle the cracked windshield

a masterpiece of crooked lines

an explosion of clarity askew

Has the narrator struck a deer? He himself can see ghosts — is he a ghost too, dead?

our zooming death

was only a few feet away

from our woods

our paradise of the natural

we never knew

that doom and vitality lingered so close

The closeness between life and death was hidden from these “natural” beings. This is the innocence lost and the bringer of feelings of vulnerability. Then the poem changes in tone for a few lines:

enlightened

rejoicing in the caution

our Father touched us with

This is a curious enlightenment, the enlightenment of the human who unlike the deer has escaped death and learned caution to help him in the future.

moments gone

when we thought

our safety expanded forever

And now the poem becomes melancholy, as the other lesson sinks in. The coexistence of the two emotions, gratitude at being still alive, sadness at seeing the beneficence of the world shattered like the auto glass, gives the poem its complexity. The image of running with the ghosts, too, is complex; the narrator seems to have remained alive yet come into contact with the dead. The troubling question is: why at the beginning does he run with the dead, with a kind of abandon that almost seems joyful, around the wrecked car? One wonders if this narrator has really chosen life as fully as the ending of the poem indicates.

One of the best poems in lapping water is a short and deceptively simple poem called the brook you gave me, which uses personification of nature to fine effect. It reads:

when it danced for you

now when I give it my body

the trees stumble

and leaves say

they don’t remember us

I can’t drink from

the brook you gave me

it tastes too much like you

but I bend down close

and listen to the water

tell me how it felt

to drip from your skin

From the first stanza it is clear that it is the body that relates fully to the stream and by extension to the emotion, and the mind can only learn from the bodily sensation. The “forest” seems to indicate a whole and natural world the narrator shared with a beloved, not necessarily but probably a lover. Now all has receded and with the loss of the beloved has come a loss of nature itself. The loss is so serious that the narrator is at first avoiding all contact with features of that world (the “brook” for instance), as it would awaken too much pain.

The use of “give” is interesting. The beloved gave him a brook; but now the forest will not take back and receive his gift, the giving of his body. He is now an observer, not part of nature, lost in yearning for it.

The last couplet reads: “tell me how it felt/ to drip from your skin”. The narrator can only speak, not experience, but he goes as far as he can with this witness to the body of the beloved, attempting to re-experience the physicality of the relationship. But this marvelous request has more in it — how did the water feel leaving the body of the beloved — did it also mourn? Did both the man and the water fall helplessly away? In another poem (when we splashed) the poet writes, “sometimes your wet skin touches me/ when I brush against soaked leaves”. Both these images bring to shivering awareness the experience of the body of another.

the brook you gave me introduces another theme found in a number of the poems in lapping water, the experience of passivity. This is strongly presented in a poem about childhood called pick a shape to form me (letter to my mother). It opens with an arresting image baldly set forth without syntax:

These bones can’t even support a sentence. The letter invites the mother to “stand in the crowds with me/ as though we still had stature”. “Stature” seems to mean reputation, standing, substance, respect, in the community. Evidently the mother and son have been much reduced by a childhood event, which turns out to be the father leaving home. The letter calls on the mother to support the son, to stand with him, but the mother never responds in this poem. He says, “let’s claim the plains of my childhood”, “let the vines grow on our old house” (bringing it to life and beauty again?).

But then comes a word sitting cryptically on its own line:

and the closing line: “lost in my father’s mustache”, a last image which seems to mean that the mother can’t help the son get out of the shadow of the loss of his father. The son doesn’t seem able to move forward alone, either, and we are left with an inability to claim the past from the parent who has blighted it.

This theme, or maybe it should be called this problem, is repeated in the most memorable couplet in the book, in broken crystal, another poem of childhood:

I am only what it burns

and the moments of hope are rare, but do arrive in the stampede has come little one, in tiny, humble, yet extraordinary words:

so you did it yourself

There are too many unconnected images in some of the poems in lapping water, especially in ointment burn and tap water. In tap water, cutting also would have added to the power of the poem, but at the same time this poem has some of the most evocative images in the book:

between years on the tombstone

and

my stripped, bare mind

The simplicity of sentence structure and the lack of ironic self-consciousness of all the poems does at times leave the reader desiring some of the edge the 21st century almost demands. The trick for Flore is not to lose, as he develops his work, the strengths he demonstrates here. Flore seems to be grappling with that in I would like to wake up in the ocean, in which he asks “where is the tide that can carry me out to sea/ without ever having to say goodbye to anyone”, but then shakes himself out of this habitual pattern of wistful emotion, pulls himself up into the meta position, and with both clarity and plenty of edge tells us:

I’d just like to be a wave

climbing up her thigh

lapping water can be purchased here; free copies of the chapbook are available upon request by emailing Dan Flore at [email protected]