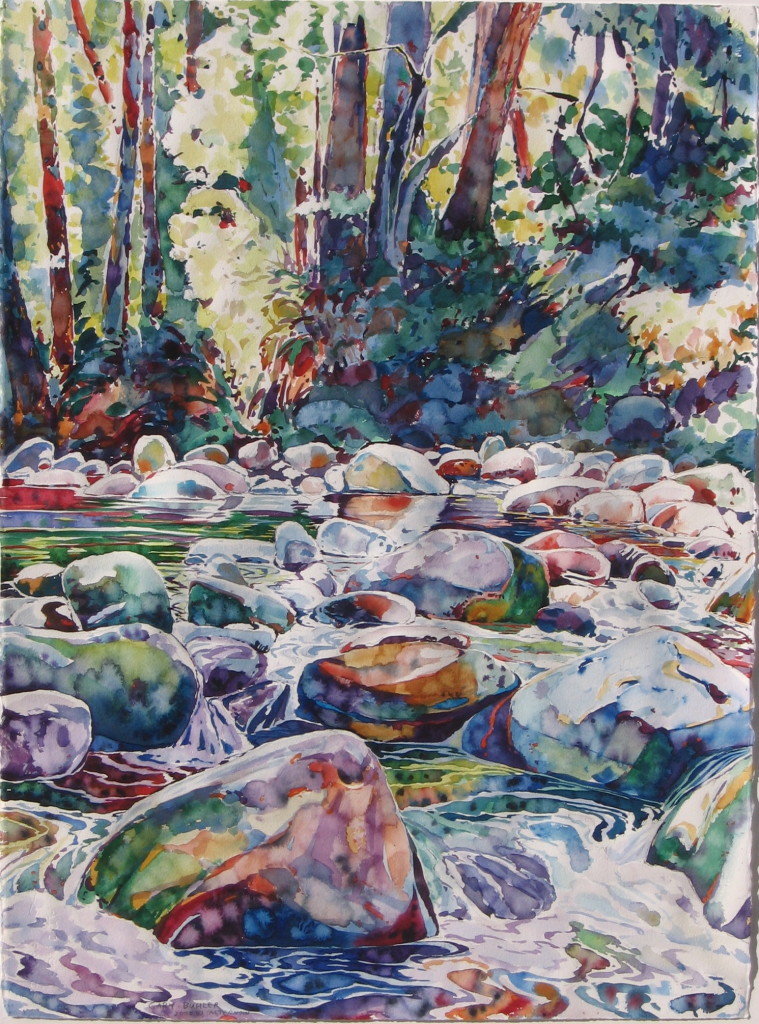

Afternoon, 22X30, watercolor, Gary Buhler

Afternoon, 22X30, watercolor, Gary Buhler

Zeitgeist

Pastor eats in the boiler room.

He finds comfort near the red heat and slag under the boiler’s belly.

He imagines sinners roasting, there, and he exults that he will never go there.

He sees his dead earthly father, there, and a deceased brother.

He lives in a Pentecostal Holiness gospel of a just God

and his wrath for sinners.

This is the Riverside Pumping Station, hard by the Ocmulgee River.

We are a microcosm of men with, mostly, high school diplomas.

I work the lab. We are all responsible for the water needs of Macon, Georgia.

I have been here 8 months. For 6 months I was on the yard gang,

cutting grass, chopping brush, repairing machines, fetching tools for the yard boss.

Now I work with beakers and burners, test tubes, an autoclave, an AM radio.

On the graveyard shift, I check the intake at the pump house, the first step

for potable water. Then I watch the huge settling basins, the intermediate step for potable water.

Then I flush the big filter pools in the long and wide filtering room, the final step

for potable water. I run tests. Somewhere in all this, I put in measured amounts

of chlorine to kill the E coli bacteria in the river water, and aluminum sulfate,

to cause the red river mud to clot and settle out.

Billy lifts weights at the gym. He started this in prison.

He stabbed a cousin to death. He is still on the yard gang after 12 years.

Clete did a few years for purse snatching. He is a full-time Romeo.

T-Eye calls him “Peehole Clete.” He has been here 8 years. He is still on the yard gang.

Jeremiah, a preacher, has been here 18 years. He is still on the yard gang.

Quince, a family guy, has been here for 3 years. He is still on the yard gang.

(This was almost 40 years ago. My life could only change at 56 when I could choose

for other people to be happy. When I could stop hating myself enough to wish them

a happy and fulfilled life. And when I could risk love.)

There are separate bathrooms and drinking fountains and eating areas

and pay scales. There is a casual evil, here, in this municipal system. It is 1975.

No one talks about it.

Every so often, the Warden brings us a cooler of speckled trout.

They get Billy to fry it up. The Warden was recently in charge, here.

He retired. They give Billy the scraps and fried flower and such.

Little Stevey is the Superintendant and main keeper of the water esoterica.

He is the head water man, a husbandman of the H2O molecule.

He started in the yard gang many years ago. He is white.

One hot summer afternoon, I was chopping weeds down in an overflow basin.

Dad Wiggins was there and Jeremiah and Quince and Billy and Clete.

I turned and saw the men stampeding away over the crest of the hill.

I felt a sting on my navel. I looked down and saw a clod of yellow jackets

on my belt buckle. I had chopped into a nest.

Dad, a Vietnam vet, moved up to a shift in the lab.

One night on third shift, Dad and I found the old and no longer used

stencils for “colored” and “white.” We stenciled colored on

the white drinking fountain and locker room door and tool box.

No one saw us do this. The engineer was asleep.

Hal “Jelly” Barker, a Baptist deacon, head of the shop,

was the first man to ever ask me if I was “born again.” I grew up

in the Methodist church. I never heard a sermon about the second birth

or about hell. Mr Barker filled me in.

I would watch the first 30 yards of each settling basin; this was where the red mud changed.

The flocculators spun like paddlewheels on a steamboat. There was a rhythm, there,

something beyond simple chemistry. Over the next 70 yards, the treated mud settled out.

I often went to the pump house around 2 am and watched the river carry mist.

I sight checked the intake grillwork to see if it was clogged with debris.

I was 19 years old in a southern town run by homicidal rednecks.

As a child, I had seen Klan violence, murder even. The seeing was for my edification.

In nursery school we sang “Jesus loves the little children. All the children of the world.”

I saw a black man lynched. I saw a white man tarred and feathered.

For the first time, as a child of 3, I wanted only to die. I wanted no part

in a life where this stuff could happen. Before I entered recovery at 53 years,

some part of me seriously wanted to die every day.

“Red and yellow black and white….”

I was 53 years old before I really came to believe on all levels

that Jesus could be trusted. I had pulled a mostly subconscious boxcar of pain

for all those years.

“This goddamn late July sun. This pitiless stretch of track. The weight.”

It is wrong to teach a child that some humans are less-than.

I knew I had to forgive the adults who coupled me to that load of soul trouble.

I knew I had carried that burden for more years than I would ever live without it.

The Macon YMCA became the Macon Health Club in order to skirt integration.

Little Stevey eventually hired a black guy with a degree in chemistry to supervise the lab.

I had left and gone back to school. Change came. Every man

could graduate from the yard gang.

_____________

Bryan Merck

Review by Dave Mehler

Bryan Merck is a poet I feel affinity for and kinship with because he chooses as his subject matter an ugly workplace where the lowest of the low congregate to work, a water treatment plant where yard gang (work release) prisoners are employed in the South, post civil rights movement but before it has had a chance to really effect change. This is the setting and the people he chooses to describe to show the workings of grace and redemptive intervention in everyday life. Both the setting and the people described form a crucible where some rest in and perpetrate “casual evil,” and others learn to love and stop hating, like the speaker, who himself graduates from the yard gang. Merck may or may not be the speaker/narrator of “Zeitgeist,” and the only reason it might matter is whether this poem stands up under scrutiny and the tests of veracity, authenticity of voice, and credible witness. I can attest it passes all these tests because I work in a landfill in the northwest which employs temporary employees who are prisoners who work and then return after work to what’s known as the RC (which has many names attributed to the acronym, but I have settled on Restitution Center). The people I work with are very similar to the ones described here even though it’s a much different time and place. How does he show the workings of grace and redemption? Partly, as mentioned before, in dealing with overarching issues of race relations in the context of a biblically literate, “Christ-haunted” South, and the hypocrisy/blindness that existed toward social justice, and loving one’s neighbor whoever he is, in that context. Merck does this with the clear eyes of a prophet and speaker of parables in gritty application, telling us stories. Related to this is the sly technique of contrasting the counterfeits against the authentic, for example, to begin the poem with a character who is reminiscent of a type of bad Puritan characterized in the typical Nathaniel Hawthorne short story, named “pastor,” who does not exemplify the transformed life characterized by love: Pastor

“…finds comfort near the red heat and slag under the boiler’s belly.

He sees his dead earthly father, there, and a deceased brother.

He imagines sinners roasting, there, and he exults that he will never go there.”

Having to work in close proximity to and manage a hellish environment, he takes comfort in placing those he holds in contempt inside it, as if he were God. Along with other hard cases described unflinchingly, he then contrasts this catalog with the life of the speaker, a true believer who in mid-life experiences a miraculous renewal (conversion) into a life transformed by love and forgiveness:

“My life could only change at 56 when I could choose

for other people to be happy. When I could stop hating myself enough to wish them

a happy and fulfilled life. And when I could risk love.)”

It’s would be too easy to write a poem like this and veer into sentimentality or moralistic platitude, and many do, but I think Merck succeeds in avoiding this, because of the life experience, maturity and veracity which informs the poem. One way to avoid sentimentality in a poem which attempts to convey a moral universe to a postmodern culture is to have a rich imagination and a biting satirical wit making humor and keen observation of others your ally, like Flannery O’Connor, a fellow Georgian, who utilized violence and the grotesque to demonstrate what she termed as “grace through nature.” Another way, which from the autobiographical hints dropped in the poem, is to have lived through long, rich and dark personal circumstances; then out of this life experience craft a narrative in the form of parable like poems which then provide a backdrop for metaphysical realities with authentic life studies that avoid the pitfalls of shallow moralism or didacticism. They tell us stories and which aren’t afraid or unable to witness to the miraculous and metaphysical events when and if they happen because they’ve earned the right through honest and believable detail to gain our attention and ear and remain credible. A third way might be the magic realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ Leafstorm, or Mark Helprin’s Winter’s Tale, which I’ve seen in other of Merck’s poems that are not on display here. Another poet who is Merck’s kinsman is David Bottoms, similar in style and narrative vein in his longer poems in Waltzing through the End-Times. But unlike Bottoms, Merck’s style is more primitive, colloquial and directed toward relating metaphysical truths and realities. Some might fault the work for this, but I wouldn’t. I see it as a point of individuality, honesty and strength—it allows Merck to take more risks and really say what he means rather than resting in a more generic or academic exercise of creating literature, playing it safe rather than speaking from the soul, gut, with passion and purpose. It’s a fine distinction, I realize, but one that can plainly be seen. Merck isn’t an academic, or teaching at the university, like Bottoms, you can just tell, and in my mind this is a strength and offers him avenues not open to those who do, because his life has been spent in other ways and now he has the opportunity to tell us about it, like a voice crying from the wilderness (from within Georgia). We need to hear more from poets like this. They feed our moral imagination.