A flock of turkeys fight

over tossed corn outside the hospital window.

Early morning stars glide

like music across violet going to gray.

A hundred times, a thousand times,

we count the fingers, a thousand fingers,

ten thousand, grip my heart.

Her skin has more colors than morning.

The turkeys are wild and violent.

Dogs scatter them at noon.

The moon brings them back

to the clearing by evening.

My new daughter should glow

from years of stored-up love.

I can’t hold her close enough.

A hot coal simmers in my gut.

_________________

Grant Clauser

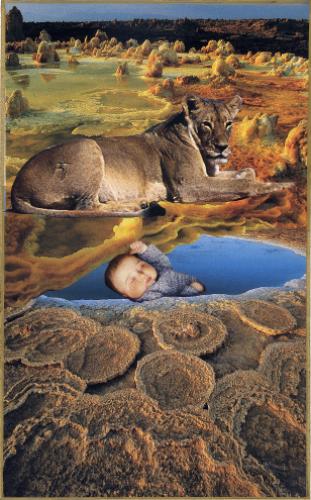

Throughout the poem, we see this technique employed of combining universal and personal experiences. The first stanza opens with grand imagery surrounding the hospital setting: “Flock of turkeys”, “morning stars”, “music”, represent the subject of a baby girl’s birth. Line four, then, begins to pull the imagery toward the personal through the description of sky, “violet going to gray”, which very much describes the base colors of the umbilical cord.

Stanza two tempers the extremely personal joy of counting baby fingers and toes with the grand imagery of “morning”. Baby’s skin, at birth, is compared to the sky.

Stanza three adds life-cycle imagery. Turkeys that are wild and violent, a mimicry of human birth, are “scattered” at noon by dogs. The stanza moves into the evening, one whole day, with a vivid moon that ushers back the turkeys, or, brings them full-circle.

The last stanza is decidedly personal. Baby’s birth is introduced. She “glow”s, like the moon in the previous stanza. The closing stanza is a great juxtaposition to the first stanza. The poem opens with universal imagery, and ends with a declaration of love. It is a perfect example of the balance this poem achieves between universal and personal.