Doctor’s Advice

He told me I’d better wear a helmet now.

OK, I said. Dad never wore a helmet.

He skied till he was eighty. He made sure,

I think, to ski when he was eighty,

even if all he did was slide a little

sideways across the fall line, stop

and watch the view come into view.

At Winter Park, you couldn’t avoid it.

It was always there, perfect, sunny,

everything packaged in white. He said,

you go ahead, Rog, I’ll meet you at noon

for lunch. It was lunch, I think, that made

the trip worthwhile. Skiing alone takes

more than concentration. There you are

in all you’ll ever know of paradise,

and your father is trying not to die

today by admitting he can’t do it

anymore. The people, the ones

who are looking for paradise again,

fly by working their turns. They know it’s near

and have now almost left themselves behind.

I’m good at pretending, or think I am,

so I told him I’d see him later,

and I concentrate, or try to,

on the turn I’m in the middle of,

the one where the wind is bending the trees,

the snow, the view, and the distance

things and everything are beginning to be from here.

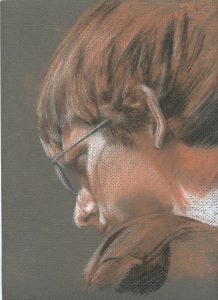

Roger Mitchell

Review by Jared Pearce

For good and bad, we compare ourselves to our forebears. This poems opens a lovely note to the past and considers how we survive the loss of our fathers. Once the father is gone, what kind of shape will the world hold, the poem indicates, and if our fathers were those who held our worlds together—as the father in the poem seems to do, leading to paradise, arranging for lunch, taking his own time as he needs to—how will the world look once he’s no longer around to get the world into a shape where we recognize it because he’s formed it that way? Sure, not everyone has had a wonderful father, so maybe the father can be a metaphor, too, for that person who seems strong enough to make the world obey; if this is the case, or a possibility, then the question of how the world will look is exhilarating, sure, but also a little scary: we’re in charge, and we’d better not blow it. In fact, we might need to put on our helmets.