Breaking Up With Hemingway

The idea that memory is a feast is

the kind of thing that you think

just before you eat your favorite

W. & C. Scott and Son pigeon

gun. Memory doesn’t sustain,

it keeps, pending removal

like a morgue, the found

deceased drawered and inventoried

and then buried or burned,

in the case of the W. & C. Scott both.

Either way ending particulate

as will this campfire launching

itself in lit ashy bits

into a cold blue Michigan

night to hang in the canopy of the poplars.

Beneath which I had

earlier kicked a faded Coors can,

nostalgia it seemed

inside of every other bounce

until one such caused a swirl

of flies to rise en masse

where bright fletching revealed a deer half

skinned and half not,

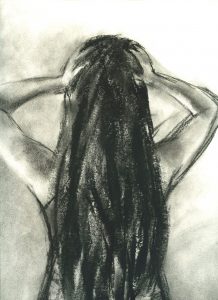

like an interrupted sketch

discarded in the leaves.

Her nose pointed to a place

just beyond reach

of where she lay.

Another cooling thing in

a woods of bodies beached

and resting to be carried apart,

piecemeal squirreled,

crow-hoarded and relic’d.

And I thought of how,

similarly looted, I had been

trying to remember myself restored,

assuming that we are each the others’

careless hunter, using a turned phrase

like taxidermy, and looking at the deer I understood

that I had been trying to see through glass eyes,

when what my cached eyes were then seeing

may have been a better preoccupation,

better than sitting a carcass,

will dissipating in a cloud.

Matt Thomas

Review by Massimo Fantuzzi

Wandering cans, “nostalgia it seemed.”

To me, child of the seventies, nothing like the act of kicking an empty can speaks of nostalgia since its unmistakable sound has now vanished from my street. When was the last time I’ve kicked one? Would I even dare to do it these days? Probably not—too unpredictable in its trajectory, may offend the neighbourhood. Better just pick it up and civilly put it in for recycling.

But here, its unpredictable landing is the opening act of a series of chain reactions/reflections. All images on offer are images of motion/intention, one-way route. “Ashy bits,” “swirl / of flies,” “nose pointed.” Everything seems on track towards a destination, and subjects become subjected/”carried apart.” Every place/experience celebrates the inevitability of its course/transmutation.

How could memory have any realistic aspiration of stopping/framing/storing this traffic jam of “bodies beached”? We are dealing with wandering cans in their hollow rattling stumble and their jittery ride of uninterrupted odd bounces. This poem offers an answer to acts of mnemonic taxidermy and nostalgia trying to get in the way of such vectorial/natural progression. “I understood / that I had been trying to see through glass eyes.” We recognize the function and the need for such attempts, but in the words of Brutus to Cassius on the eve of their Philippi, “the end is known” —no will can ever change that. Far from being bulletproof, memory does what it can: “it keeps, pending removal”—but the time to move again and to dissipate “in a cloud” always arrives.

Review by Jared Pearce

While I like the considerations of memory and its effects in the early portion of the poem, after we get to the deer’s carcass, the poem really coheres together and pulls the more philosophical considerations in the opening lines right to the world of lived experience that happens as soon as that Coors can is kicked. The movement in the poem, then, demonstrates the very idea at the heart of the poem, the way memory matters to us and how we survive moment to moment.