I Take Up Running After You Are Gone

by Ellen BihlerSunday

Whether by instinct gone awry,

suburban sprawl, natural selection,

or plain stupidity –

in a roadside ditch a doe’s body stiffens.

Flying low and at the northernmost edge

of its summer territory,

the American Black Vulture picks up the scent

of ethyl gas.Monday

Fur pulled away, red breast meat striped

by barreled rib cage.

Featherless heads bobbing,

eyes glazed with excess.Tuesday

Side to side, so many birds now

they obscure the dead in a living blanket.

Scavengers even of their own bodies,

they drip feces down legs;

cool themselves as the liquid evaporates,

Across the street, two sentries on a pole.

Faint hisses; no song.Wednesday

A few stragglers.

A fur coat strewn in the dirt.Thursday

A scapula,

a single long bone,

the skull with lower jaw missing.Upon returning home,

I shower off the stench of running.

Trash bag in one hand,

box for Goodwill in the other,

I enter your bedroom to pick through

what remains.

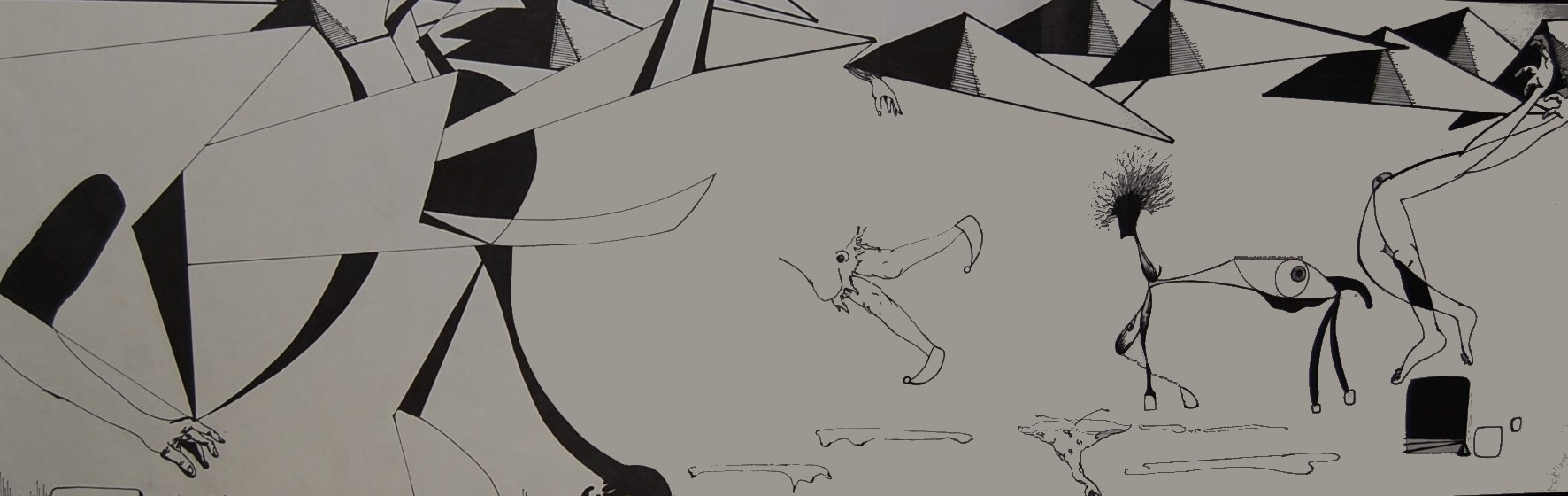

Acquiescence of The Beast and Ensuing Malfunction by Jon Zowalki

Ink on Paper

Discussion by Brendan McEntee

This is a clean well-wrought poem. Like the strong resounding tone off of fine crystal, it’s pitch is perfect, . The strength of this poem isn’t that the metaphor that the carcass is a stand-in for “the gone” rather, the narrator is aware that this is what’s happening. This is the grieving process laid out and observed by a recriminating “I.” We don’t know who “the gone”–it could be an addicted child, it could be a home-hospice parent, or a visiting friend/relative: the truth of it is secondary to the reaction and understanding of the narrator who uses action (running) and observation (specifically, doe carcass) to come to terms with unhappiness.

The title almost misdirects us. The narrator has “taken up” running, which it’s assumed is for health benefits, as well as the subtext of running “to” or “from.” As this is a new activity, the opening stanza throws us, much the way the narrator must have been thrown coming across this scene:

Quote:

Whether by instinct gone awry,

suburban sprawl, natural selection,

or plain stupidity –

in a roadside ditch a doe’s body stiffensThrough their title the narrator has engaged in a healthful activity and comes up right against death. The next few lines work as a metaphor for a number of things: drug addiction; the ravages of old age; the failure of a sibling/close relationship or the death of a child, where the doe is the child/parent/sibling and the relationship & drugs/death/old age/ are, the external forces of the world. The following lines speak to this:

eyes glazed with excess.

Scavengers even of their own bodies,

they drip feces down legs;Faint hisses; no song.

A few stragglers.

A fur coat strewn in the dirt.Again, the narrator has taken up running, affirming life and is almost immediately faced with the grimness, yet wholly natural processes of entropy and life. By the end, there are only physical “remains” to be cleaned up and carted off. The effictiveness of this poem is that the poet doesn’t speak directly to this at all: we have a runner, a decaying deer, and cleanup. The resonance is in how the poet uses that language to effectively convey the loss (be it spiritual or physical) of the other person. We’ve only two instances of “the Gone”: the title and the next to last line, but the poet is skillfull enough to have them haunt the poem, as the narrator is haunted.

If I had to pick a word to describe this poem, it would be “elegaic.” Not a word misplaced. The poem and poet serve the human experience well.