Conversation with Featured Artist, Mark Terry

conducted by Dave Mehler for TCR

TCR: Can you tell us basically what you’re up to in building kilns and making art with clay and fire and how you got started with that? In other words offer up a brief history and maybe touch on how you discerned your calling as an artist, and in this medium in particular?

Mark Terry: I am currently planning the construction of 3 different kilns. From smallest to largest (in terms of scale of the project), they go as follows:

1. Small ‘soda kiln’ to complement firing options on campus. Spraying a soda solution into the kiln at peak temperature can create unique and very attractive glaze effects. However, salt derivatives are very corrosive to brick, so this isn’t possible in the primary studio kiln. We’ll assemble a small, portable version with interested students during the Fall semester.

2. Small wood-fired kiln. Parishioners in my church have a farmstead up on Chehalem mountain. Both potters, but unable to afford a high-fire kiln and interested in ‘sustainable ceramics,’ I have designed and plan to construct a wood kiln just big enough to support a small ceramics practice – as well as the growing interest in promoting ‘making’ as an integral spiritual practice in our church community. Their place will be maker-space for them and for parishioners, and fueled by wood off their property, the kiln will provide a forum to gather around communal creation. That project is slated to come together in the late winter this year.

3. New wood-fired kiln to replace the Noble Hill Anagama. I am currently working on the ‘firing compound’ in preparation for Fall construction of a new wood kiln for my own art practice and as an extension of the George Fox ceramics program. This will be sited just a few miles from campus on the edge of North Valley at the home of colleagues who offered up space for communal creation. Moving from ‘anagama’ to ‘bourry box,’ style, the new kiln will be designed for more efficient fuel-consumption and enhanced surface effects from the firing process.

My beginnings with clay are very much as described in my thesis. I initially took a pottery course to explore one of the media I might need to be conversant in as an art teacher. But the moment I felt the clay ‘come to center’ in my hands, I was addicted. I often say that I am rarely so alive – or feel so ‘complete’ as when I am elbow-deep in clay and busy in the act of creating with this wonderful, yet mundane substance. I feel an intimate and immediate connection with my Creator – whose act of initial creation is described in most cultures across our planet as breathing life into clay – that nothing else can match.

My story of calling to being an artist has a similar ring. While I majored in art in college, I was ill-prepared by either experience or education to make it into a vocation, and went into business. However, despite early success in the corporate sphere, the work wasn’t fulfilling, and I had ‘mid-life crisis’ at the ripe old age of 24. The simple fact is that nothing else I’ve done has ever provided me the satisfaction as making art and helping others discover their own inner artist.

TCR: As a poet who has tried to run a business ‘on the side,’ I am very interested to know how you switched gears practically to move from business and a corporate environment to teaching. Can you elaborate?

Mark Terry: Despite significant early success in the corporate world, I felt something was missing, and entered into a ‘dark night of the soul.’ The root of problem was that while good at the work I was doing in operations management for a large insurance company, I had to really contrive to find any real meaning in it. Sure, customers got better service, employees found more success and satisfaction in their work, and I was employing my creative gifts in organizational problem-solving…but I wasn’t making art. I’d go out for walks in downtown Portland during my lunch break and would almost invariably find myself drawn into an art gallery or art supply store. And I told myself that ache in the pit of my stomach was hunger, despite the fact that eating did little to make the feeling go away. After some months of this, and as I was being groomed to expand company operations by opening a branch in some Midwest center – think some flat, brown place like Omaha or or St. Louis (as a native Oregonian, my thought was “God-forsaken place like Omaha or St. Louis) – I began to despair. To get a little break from what seemed increasingly bleak, my wife and I decided to get away for the weekend to go skiing in Bend. As we slowed down to negotiate the charming Central Oregon town of Sisters, I exclaimed in frustration that the way things were headed we’d never be able to live anywhere like this!

* Note that this was the early 80’s, and in Oregon we were deep in the throes of a REAL recession (as opposed to the one we’ve recently weathered) and I’d spent 6 months unemployed before landing this job.

NEVER SAY NEVER.

At that very moment, the sun broke through the January snow-cloud cover in Sisters, and a brilliant beam of light illuminated the crystalline air to bathe the local high school in light like a spotlight. ‘Sounds 100% corny, to be sure. But as that happened, I immediately flashed back to 8 years earlier where on the occasion of my first time skiing, I looked down on 3 and 4 year-olds cavorting on the slopes and swore to the surprised stranger next to me that I’d NEVER be a teacher! Having been raised in the household of a small town middle school teacher extravagances like skiing were out of the question. My response to such humble upbringing was to want something more for my own future family.

Fast-forward back to Sisters and the school in the spotlight. At that moment, my wife and I looked at each other and pretty much exclaimed together that every town in America has to educate its children, and we could go settle anywhere we wanted if I would consider teaching.

It was like being hit upside the head with a 2 x 4 – or maybe being knocked off your ride on the way to Damascus. At that moment, my head was ready to listen to my heart, and I was able to see that the root of my success in business lay in my natural inclination to teach those around me, and that like Jonah, I’d been running away from something I had been called to. We immediately took steps to leave our jobs in Portland, and I returned to school to obtain the necessary credentials to teach art in public school. From that day, I’ve never turned back, and I’ve been living and teaching the path of the maker ever since – 34 years, now.

TCR: If you were to break down the process of your art to fire and clay, how would you rate the pleasure you derive proportionally to each? Another way to rate it would be as process or completion and end product.

Mark Terry: There are potters who see the firing process as little more than a step between beginning and end. I LOVE the forming, shaping, editing, finishing process involved in making. But in contrast to some (and in concert with all the best – I think) I see the firing process as where the real magic takes place. Whether with wood, electricity, or gas, the transmutation of substance – the change from dried mud to stone, and later, the melting of media to glaze the finished form – is simply magical to me. That lies at least in part to my limited control over the process. I can stoke more wood or turn up the gas, but it’s the power of intense heat – the trial by fire – that transforms the temporal work of my hands into something permanent. Think of it. What might otherwise crumble to the touch, or melt back into mud with exposure to water is changed into something that could be uncovered by someone 10,000 years from now, and thereby communicate something to them, regardless of language! I love both the making and the firing, all the process from start to finish, and will claim that the end-product is an inextricable reflection of the entirety of the process.

With that in mind, I find particular joy in firing processes wherein that journey is more evident in the end-product; wood-fire, raku, and primitive pit firing, all of which leave the language of the firing process in the surface of the finished work.

TCR: Another question in the back of my mind is where does all your art end up? After seeing so many images, and understanding that the process is a big part of it, and the functionality/utility of bowls, bottles, plates and cups, are you exhibiting, selling or giving away much of this work?

Mark Terry: Most of my functional pottery ends up as gifts. Working at a college leads naturally to lots of wedding invitations. Special events and charitable activities are always in need of contributions, and then the special life occasions of friends, family, colleagues and church need to be celebrated. While I sell some functional work, the bulk of my commercial practice is sculptural.

My primary sales venue is the Art Elements Gallery here in Newberg. I also have work in the O Zone Gallery in Newport, and show frequently in the River Gallery in Independence, the Cannon Beach Gallery, here at the University and the various galleries at the Chehalem Cultural Center. Sadly, my galleries in Eugene and Portland didn’t survive the recent recession. I show less frequently in exhibitions.

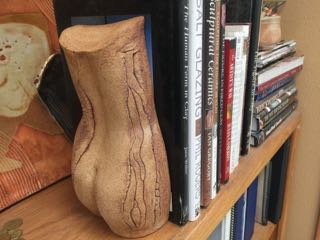

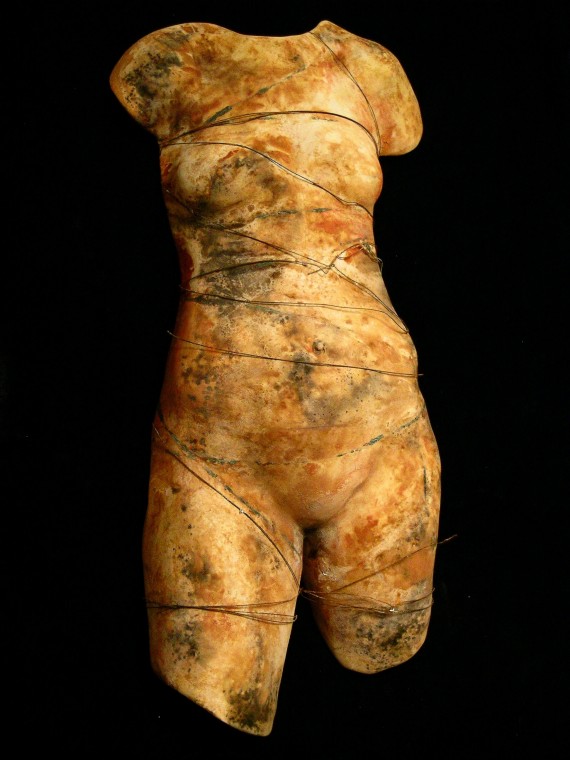

TCR: Also I have a hard question to ask after seeing your thesis and so many images of work that you’ve shared with me. It’s difficult to frame in such a way as to not be or sound offensive and partly I want you to spell out the answer for me and possibly I need you to spell it out for our readers even more. Knowing you and having dipped into your thesis, and knowing our community which involves Newberg and George Fox University, I have some guesses about where you’re coming from, but basically the question must be asked: One of your obvious obsessions in your art is the torso, male and female, stripped of head, arms, legs and clothes. Often but not always scarred, decorated or fractured and plated. How would you respond to an uninitiated observer who walks into a show and accuses you of blatant sexual objectification, especially of the female? Just what are you up to and what are you thinking and where does art and spirit come in, if at all? Perhaps this has even happened?

Mark Terry: This last question is difficult to answer without a more lengthy discussion, but let me try to condense it some. Yes, knowing that my academic community is a conservative Christian enclave in a town founded by conservative Quakers might suggest potential for some dynamic tension. By and large (and really with only rare exception) this work has been welcome in my community. My interest in the human figure is actually rooted in my personal faith – in the belief that we are all made in God’s image and that as such we are, as scripture notes, “fearfully and wonderfully made.” The historical distrust of our own form among conservative Christians leads to all kinds of problems that my work intends to challenge and discuss. To begin with, it isn’t the body that is at the root of improper interest, it’s the heart of the viewer. And my sculptures aren’t ‘nude bodies,’ they are fearfully and wonderfully made objects. They are sculptures. Objects made with reverence, and with recognition that as I craft them, I have been gifted with the opportunity to reenact the Creation story. And as I do, to gain a wee bit of insight into both the nature and inexplicable kinship with my own Creator. The titles almost always make reference to deities from classical mythology, many of whom were recognized in their time as the embodiment of natural beauty, and christened into the ‘sacred vessels’ series. Although I seek and find beauty in all human forms – male, female, young, old, large, small, skinny, plus-size, etc., and have worked in each of these genres, as a pretty average heterosexual male I can’t help but be captivated by the beauty and mystery embodied in all that is feminine, and believe that perspective has informed some of my best pieces. Is that objectification? While some might say so – my own take is that it’s simple, honest – human – interest. And if looking at anything and making an object inspired by that view can’t help but be ‘objectification,’ I guess my fellow sculptors and I must, by definition, stand guilty as charged. Mea culpa.

The textures on my figurative work are most often inspired by the gorgeous natural landscapes I am blessed with in Oregon, whether the topographical lines inscribed in hillsides by vineyard or the birds’ eye view of watercourses and game trails. The ‘fragmentary’ nature of many of the pieces pays homage to my other great inspiration, art history, as I reflect on the broken remains of such masterpieces as Venus de Milo, Nike of Samothrace, and Mycenaean bronzes. I love history and how the little bits and pieces that survive tell us volumes about the people and times from whence they came. I also believe that every piece is fully ‘clothed’ by the natural patina provided by its baptism in fire and the powerful blend of science and mystery that comes together in the alchemy of that process. And as noted earlier, I get a kick out of the notion that perhaps something I’ve made will be rediscovered 10,000 years from now and inform future archeologists or art historians of my interest in even older artifacts.

This work also speaks in metaphor, as I believe we are all flawed and broken in a variety of ways, yet still beautiful works of art as we reflect the Imago Dei. As my aforementioned love for surface texture is applied to the work, I seek to challenge viewers to learn to see features like scars, facial wrinkles and stretch marks as beautiful reflections of hard-won experience in living – or as I recall from my own childhood curiosity about grandparents’ war injuries – battle scars and missing limbs as medals of valor and personal sacrifice rather than disfiguring injuries. Like intentional marks like tattoos and ritual scarification, the marks borne on our figures illustrate the narrative of life experience.

Does the viewer always see my intentions or perceive this language? Nope. Although, to be honest, I’ve really never actually heard from anyone who found their perception of nudity troubling. Either it’s just not that big an issue in our sensualized multi-media world, or they’re uncomfortable speaking out about it. On the contrary, I have often been thanked – and almost always by women – for treating bodies as works of art, rather than sources of shame narratives. I have also been honored on more than one occasion to encounter a viewer/participant in the moment of having been moved to tears by this work. For an artist, evoking that kind of emotional response is a lifetime achievement award.

TCR: As professor at George Fox U. for many years, and serving in the past as head of the Art Dept., a big part of your vocation is not only as an artist but also an educator, mentor, and at the very least an administrator but also a director of the Art Department and visionary of the program and curriculum. Would you be willing to tell us what that’s been like and share some of the joys, frustrations and opportunities?

Mark Terry: I’m not sure how to answer this question short of a good-sized book. What I can say is that it has been the foremost challenge of my life to build this program – from scratch. When I arrived there wasn’t so much as a proper classroom, never mind the resources for a fully developed Art & Design. Growing it from ground zero has been the source of untold delights and satisfactions, as well as a fair share of frustrations. I can summarize and say that despite notable growth each of the last 20 years and becoming the 5th largest major concentration in the institution, it has been nigh unto impossible to convince decision-makers that there is legitimate and sustained demand for art and artists in the 21st century academy and economy, and that my constituents deserve the kinds of investment that have been thrown speculatively at high-tech and healthcare-related initiatives. My institution has thrown millions of dollars at new programs to attract yet-unrecruited students while failing to acknowledge that those initiatives have been funded in part by the millions of tuition dollars paid out by art majors working with mostly inadequate and improvised infrastructure.

Despite the frustration of ‘living off scraps,’ I get deep satisfaction from the success stories of my alumni, and the knowledge that the investment in each of them pays it forward over and over again as they take salt and light into the world. Artists of all stripe are in demand in the marketplace, and our majors enjoy a remarkable employment rate – FAR better than mainstay majors like Business. At a recent commencement ceremony, I enjoyed watching 33 majors cross the stage to receive their diplomas, 30 of whom already had job offers in hand. Ironically, the 3 that didn’t were our top performers, and they simply decided not to dilute their ‘finish’ with job hunting. Within a month we could claim 100% employment. As artists, designers, teachers, arts administrators and entrepreneurs our graduates are shaping their respective communities.

TCR: Have you been involved at all with the Honors Program started a few years ago?

Mark Terry: Modestly. I serve on the academic committee that provides oversight for the program. While delighted with the unqualified success of the program, I have been an advocate for inclusion of the fine arts as vital elements of the ‘textual resources’ of our ‘great books’ program. Our honors students should be visually and aurally literate – knowing how to ‘read’ an artwork and to be conversant with the masterpieces of art that correspond with the great books they’re working with. We have yet to do more than scratch the surface on this count, but I am hopeful that now that we’ve graduated our first cohort, we’ll be working on qualitative enhancements of this sort.

TCR: Poets are often discouraged by the indifference of the culture at large to read and engage with and appreciate their chosen medium of artistic expression. Do you ever feel like you’re working in a vacuum, or feel perhaps working in the medium of ceramics and sculpture that you’re not getting the attention of visual artists? Or have I got it reversed, and perhaps your work is even more well received by peers and colleagues working in graphic and visual arts?

Mark Terry: No, you’re pretty much right on track. Film and popular music get the majority of the attention of the masses, while art forms like poetry and pottery draw the attention of minute but dedicated specialized audiences. And, as you suggest in the visual arts, rather like painting, while sculpture enjoys higher esteem, ceramics is pretty much at the bottom of the arts food chain. My experience has led me to the conclusion that anything that has ‘utility’ in the arts gets relegated to either craft or commerce. The more useful it is, the less value it commands. This, however, is where I would direct you to the essay I’ve tagged-on at the end of your questions, where I discuss the importance of ‘making’ in the more universal balance of our world…please go there for a more thoughtful reflection on this theme.

TCR: As a tag on question, what do you hope a viewer takes away from your work after viewing an exhibit? Obviously, some of your work has functionality as cups, bowls, and bottles, but I’m speaking of the more decorative, expressive, meditative or spiritual work.

Mark Terry: A subtle sense of satisfaction that comes from encountering beauty. I have twice encountered a viewer at the moment wherein they had been moved to tears by one of my sculptures. Lifetime Achievement Award for any artist. And while I don’t expect a well-made tea bowl to move the user to tears, their act of returning to it each day to make the intimate connection with their lips as they draw warmth and sustenance from their favorite beverage – that is as high an achievement as I could hope to earn from a patron.

TCR: Earlier you mentioned the importance of faith to the institution you work for and personally in your own art and expression. Can you tell us more about how that works itself out personally and through your artistic expression?

Mark Terry: While perhaps better answered in the essay that follows, I’ll say that I believe making in all its forms represents a humble reenactment of the original act of creation, and that when I engage in making, I enjoy a subtle sense of oneness with the Creator of the universe. It is for me, an act of prayer and devotion – a chance to speak in a spiritual language that expresses my innermost being in a way that transcends the bonds of mere words.

TCR: And in this regard what are your hopes and fears?

Mark Terry: Fear first, that as we become increasingly devoted to digital media and our hands become ever more removed from making of all sorts (think 3-D printing, robotic construction, etc.), that our culture will lose some of its connection to making, and thereby lose more and more of what I believe makes us innately human.

I have the same fear connected to the increasing focus on STEM in our educational system – that we are raising generations of students who are visually illiterate and creatively impaired, ultimately responsible for the creative retardation of our children. With all kinds of research validating the importance of creative play, inquiry and performance in development of intelligence, it is simply unconscionable that we have progressively limited and in many cases eliminated the arts in our schools.

My hope is that as human beings we all have the ability to sense something missing and actively seek remediation – that more and more we will try to fill that ‘God-shaped’ hole in our hearts by seeking out alternate sources for creativity and arts education in private and public sectors. Private instruction, community colleges, cultural centers, churches and public arts programming all provide rich opportunities to fill the growing void created by what I am bold to call abject failure in our educational system.

TCR: So many times encounters with people and circumstances or opportunity directs people with gifts at just the right time positively, and sometimes negatively as well which a person can turn to their advantage down the road. Your introduction to ceramics and sculpture was like this. For some, the chance encounters with just the right person or timing seems like a stacked deck and others an uphill battle. I’m wondering what advice you might offer to aspiring artists that might help them navigate these extremes, or help to get them past the thinking or talking stages, and help them get past the chance or happy or unhappy accident stages just a little bit? I know you’ve got stories… and lastly, any questions you wish I’d ask, but didn’t?

Mark Terry: Yes, and they might be answered in the essay that follows, recently published in CIVA’sSEEN Journal. Especially the final 2 paragraphs. POTTERY/PRAYER (http://civa.org/resources/civa-publications/seen-journal-xvii-practice/.)

One of my life’s most poignant moments came during my first lesson at the potter’s wheel. I’ll never forget how my teacher laid his hands over mine and helped direct the pressure needed to guide the clay into center. That moment when the clay ‘found’ center was absolutely electric. It tickled my innermost being in much the same way as feeling the faint kick of our first child in my expectant wife’s womb. Life yet-to-be-born was announcing itself!

From that day when I first felt center I have been at my core, a maker – a shaper of clay. Every time I sit down at my wheel, in a modest yet incredibly powerful way I am privileged to reenact the Genesis story as I take this most unpretentious of all media – raw earth – and breathe into it both life and purpose.

I am never so happy as when up to my elbows in clay. Why is that? At one level, when deep into making, I know I am doing what God created me to do. I feel a kinship with the famous runner Eric Liddell, who said so well in the movie, Chariots of Fire, “…God also made me fast, and when I run, I feel His pleasure.” I believe that artists are blessed with a oneness with their Maker as they give birth to new work. There is something special about bringing substance out of void that provides hands-on insight into the meaning of ‘Word made flesh,’ and unique intimacy with our Creator. When approached from this mindset, the work we do becomes a special kind of prayer – the prayer of incarnation.

Creating in clay also has its own sense of liturgy. Each session begins with ritual preparation, as clay is wedged and body seeks the balance necessary for the act of centering. In the best of work there is listening, as artist seeks oneness with medium during the shaping, each telling the other where it wants to go. And of course, there is the waiting. Waiting for the clay to dry, for the kiln to climb to temperature, for the fire to animate glazed surfaces, and for all to cool down again and appear as finished work.

With regard to ‘incarnational prayer,’ while there are a handful of better-known directions for artists in scripture, having been raised in evangelical traditions, it wasn’t until later in life that I discovered the intertestamental book, The Wisdom of Yeshua Ben Sira, (or merely Sirach). Greek church fathers called this work “The All Virtuous Wisdom,” and Sirach is included in the Septuagint, as well as the Biblical canon of both Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions. Here is what the rabbi has to say about makers:

So every craftsman and workmaster that laboreth night and day, he who maketh graven seals, and by his continual diligence varieth that figure: he shall give his mind to the resemblance of the picture, and by his watching finish the work. The noise of the hammer is always in his ears, and his eye is upon the pattern of the vessel that he maketh. He setteth his mind to finish his work, and his watching to polish them to perfection. So doth the potter sitting at his work, turning the wheel about with his feet, who is always carefully set to his work, and maketh all his work by number. He fashioneth the clay with his arm, and boweth down his strength before his feet: He shall give his mind to finish the glazing, and his watching to make clean the furnace. All these trust to their hands and every one is wise in his own art. Without these, a city is not built.

And they shall not dwell nor walk about therein, and they shall not go up into the assembly. Upon the judges’ seat they shall not sit, and the ordinances of judgment they shall not understand, neither shall they declare discipline and judgment, and they shall not be found where the parables are spoken: But they shall strengthen the state of the world, and their prayer shall be in the work of their craft; applying their soul, and searching the law of the most High.

Sirach 38:27-34, DHV

In this ecclesiastical passage, the wise rabbi claims that the work of makers defines the very essence of civilization. Further, he asserts that our work is too important for our time to be wasted on such things as governing. Rather, our work is considered a prayer so important that it serves to ‘strengthen the state of the world!’ So for all intents and purposes, the work of our hands is a special kind of communion with the Ultimate Maker in which we are privileged to be active participants in the work of keeping the fabric of civilization intact.

Not long ago, noted artist and author Makoto Fujimura visited my community to lead a lively discussion about our responsibility as ‘caretakers of culture.’ Pitted against the daunting might of Hollywood, Madison Avenue and social media, I have little faith that I have the means to have much influence on our culture. However, God’s word promises that every time I shape clay I engage in the powerful prayer of incarnation, and that thereby, the work of my hands plays its role in culture care. That knowledge drives me to my studio, reminds me of that first magical spark that set my own creative pursuit into motion, and most importantly – that even the most humble tea bowl has its part to play in maintaining the state of our world.

Mark Terry M.F.A., M.Ed.

Professor of Art, George Fox University

TCR: Thanks Mark, for your time and for sharing your artwork with us at TCR.